The Obama Tragedy

Embracing “authentic” blackness, the president created an Era of Ill Feelings and damaged America.

Autumn 2016

There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America,” declared Barack Obama in the 2004 Democratic Convention keynote speech that made him famous. “We are one people, all of us pledging allegiance to the stars and stripes, all of us defending the United States of America.” Who, listening to the young, graceful African-American senator, whether sharing his politics or not, could not have felt uplifted by the thought that perhaps the half-century struggle for civil rights had finally succeeded? And when the same senator, four years later and still very young, won election as president, even those who despised his politics couldn’t suppress a thrill that Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a republic based on the proposition that all men are created equal had finally become reality with no asterisk, no reservation. Almost a century and a half after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, with 620,000 young Americans dead in the war to make men free, the longed-for post-racial America seemed to have arrived.

Vain hope. Obama drove the races apart, reversing some of the progress that so many earnest civil rights supporters had won, some even at the cost of their lives. Instead of uniting the country, Obama divided it almost to the point of fracture, pitting group against group with a self-righteous certitude that he alone could see the right as God gives us to see the right, and that all who disagreed with him deserved withering scorn. Unlike the Era of Good Feelings that James Madison bequeathed to the country when he left the White House, Obama has already ushered in the Era of Ill Feelings, fanning every low, intolerant, and ignorant impulse in the American heart. Whether history will judge that his reversal of racial progress and the divisiveness he has inflamed make him the worst of our presidents we can’t yet know. But it is worth looking back to ask what made him so overbearing, so contemptuous of the spirit of our Constitution, and so dismissive of the idea of American exceptionalism that he pretended to embrace in 2004.

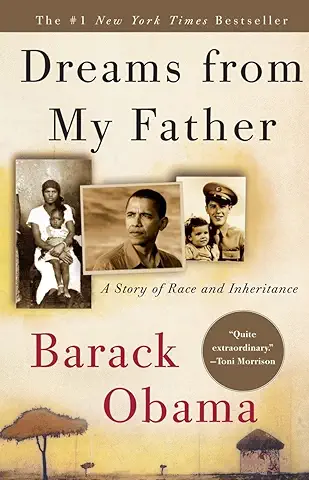

These questions are easier to answer with him than with most presidents, for, mystified about exactly who he was, he couldn’t stop talking about himself or his beliefs. Two thick books record his musings—an interesting autobiography, Dreams from My Father of 1995, and a 2006 policy tract, The Audacity of Hope, so numbingly dull that critics have doubted that both bestsellers flowed from the same pen. Perhaps more buyers wished to applaud the charismatic, meteorically rising black politician than to read him. Still, both books are deeply revealing, often despite themselves, and the picture you can piece out from them enlightens. Continue reading