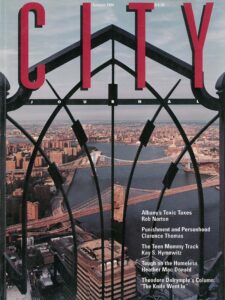

[Editor’s note: It was thirty years ago that I wrote this introductory column to the first issue of City Journal that I edited. As it seems remarkably pertinent three decades later, I thought I’d mark the anniversary by reposting it.]

An amazing coincidence, I thought, as I read Vincent Scully’s analysis of an obscure Renaissance painting in his absorbing critique of urban modernism on page 75. For years I’ve had a print of that picture hanging over my desk. Showing a walled Italian city bustling with cosmopolitan activity—from merchants and bankers doing business, to a lecturer addressing an audience, to construction workers building, to girls dancing in the square—it is a representation of the urban ideal, setting forth what makes cities special today no less than six-and-a-half centuries ago, when Ambrogio Lorenzetti first laid out his then-unfaded colors on the Siena city hall wall.

City Journal articles typically focus on urban problems, exploring their origins and their solutions. But it’s also important to make explicit that behind the criticism lies just such a passionately held positive ideal of what a city is all about. The ideal is simply this: cities are hothouses of humanity, cultivating human potential to its fullest development of excellence and variety.

That’s because cities, at their best, are arenas of opportunity and ambition and achievement. Their sophisticated economies allow individuals to fulfill their talents as anything from artists or attorneys to zoning consultants or zookeepers. The collaboration and competition that spring from large concentrations of people push skills to the greatest possible refinement, fostering the best singing, neurosurgery, or dealmaking of which mankind is capable. And because of the opportunities they generate, cities endlessly renew themselves by drawing in the talented, energetic young from everywhere else.

They draw in a revivifying stream of people and from the world’s far-off places, to which they are linked by an international web of trade, represented in Lorenzetti’s painting by the merchants coming and going with their pack animals. That connectedness makes cities temperamentally hospitable to newcomers, even foreigners, willing to let them put their energies and abilities to use.

Above all, cities are realms of freedom—freedom from the narrow constraints of rural and small-town life; freedom to invent and dramatize yourself, to choose your friends, to direct your life, to better yourself, to enjoy privacy and anonymity, to think new and dangerous thoughts—which is what makes cities engines of invention and progress. Cities offer freedom, too, from the merely utilitarian facts of life: because of their wealth, they allow people to create a world that embodies the highest aspirations of what human life can be, in art and culture, in splendid buildings, in public works, in the work of art that is the city itself.

Lorenzetti’s painting, which takes up a whole wall in Siena’s city hall, is titled The Effects of Good Government. On another wall is its companion, The Effects of Bad Government, in which justice is dethroned, violence and murder reign in the streets, people cower in their homes, buildings decay, nothing good flourishes. It’s an important message for those who inhabit city halls and other seats of authority. Cities are man-made constructs; and the character of the manmade order that prevails shapes the kind of life individuals can live there. People concentrated so closely together can produce discord and squalor no less than harmony and splendor.

That order-shaping government operates in many ways. It molds the character of citizens and their collective life through the administration of justice, as Clarence Thomas’s article (page 41) explains; through the maintenance of public order, as Heather Mac Donald shows (page 30); through the administration of institutions like the foster care system, discussed by Rita Kramer on page 63; through the way taxation fosters or blights business activity and job creation, as Rob Norton analyzes on page 10; even through the ways the reigning culture encourages people to think about their lives, as Kay Hymowitz outlines on page 19 or Theodore Dalrymple discusses on page 92, in the first of what will be a regular column in City Journal. Informing all these stories, and all that City Journal does, is a vision of urban life as it might be shaped, a life in which all citizens participate in the humane community that the Italian painter envisioned three centuries before New York was born.