by Peter Wood

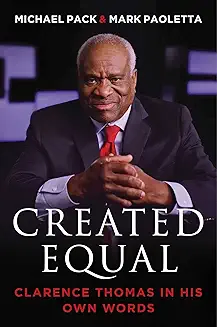

Clarence Thomas graduated cum laude from the College of Holy Cross in Massachusetts in 1971 and received a J.D. from Yale University in 1974. His memoir, My Grandfather’s Son (2007), testifies to a much deeper educational journey—one that began under the determined watch of his maternal grandfather in Jim Crow Savannah and that culminated in his ordeal during the 1991 Senate confirmation hearings. In between came his appointments as head of the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Education, chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

What he learned in those positions was significant, but not transformational. The transformational moment, we learn in Myron Magnet’s new book, Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution, came in 1980, “after he read through [Thomas] Sowell’s works, registered as a Republican, and voted for Ronald Reagan.” He was drawn by Reagan’s “promise to end racial social engineering.” Thomas had had a bellyful of that at Yale and had concluded that “blacks would be better off if they were left alone” instead of being conscripted into the utopian schemes of liberal politicians.

Needless to say, this wasn’t an idea he picked up from his teachers at Holy Cross or Yale, though it did owe something to his grandfather. Moreover, it prepared him for the opportunity he had at the EEOC when “he hired as special assistants Ken Masugi and John Marini, students of political philosopher Harry Jaffa.” Masugi and Marini introduced Thomas to texts that deepened his knowledge of the American founding.

Magnet’s book devotes a chapter to “The Making of a Justice,” which rightly reaches its climax with the attack led by Senator Joe Biden that riveted the nation during the October 1991 confirmation hearings. It was, of course, a trial by ordeal. How much vitriol and character assassination can a man stand? What had happened to the civility and decorum of the world’s greatest deliberative body?

Part of what Thomas took from the Anita Hill accusation-fest was a new determination to uphold the real Constitution of the republic, rather than the patchwork of extra-Constitutional shortcuts, “emanations,” inventions, and betrayals that progressives had cobbled together over the years. This haystack of judicial law-making is ferociously defended, and not just by the progressives who built it. Americans have become accustomed to rule by a high Court of unelected judges who can have what amounts to the final say on any issue they choose.

Thomas reached his seat on that Court with a disposition to dispute what most regarded as “settled law”—settled in the sense that the Court had spoken in cases that had become “binding precedents.” How binding a precedent might actually be, however, was always an open question. The Supreme Court now and then overturned previous decisions, though it usually tried to explain this by citing still other precedents.

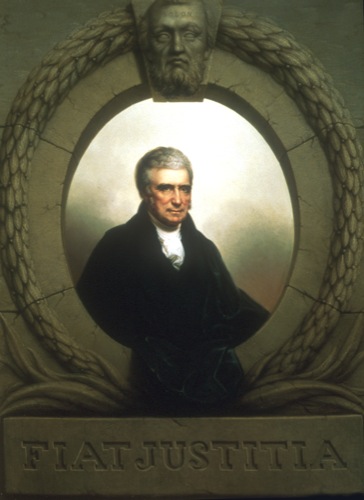

Asignificant stretch of Magnet’s short book is a chapter—“Who Killed the Constitution?”—that provides deep background on how the U.S. Supreme Court, step by step, shifted from interpreting the Constitution to what we laymen might call making stuff up. No doubt it is more complicated than that. Making stuff up usually involves a lot of dignified chin pulling and circumnavigation of common sense. And making stuff up isn’t some newly discovered human faculty that emerged on Woodrow Wilson’s birthday or when Justice Owen Roberts weighed FDR’s Court-packing plan and decided he liked the extra-Constitutional New Deal just fine. Making stuff up is what powerful, self-interested people always do when they can. Absent a strict division of legislative, executive, and judicial powers and a system of checks and balances, rule by fiat is inevitable.

Magnet takes us back to the post-Civil War era during which the Supreme Court eviscerated the Fourteenth Amendment in its Slaughter-House Cases (1873) and Cruikshank decision (1876). The Slaughter-House Cases stripped Southern blacks of most of the civil rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. It did so by “interpreting” their rights as citizens to be only their rights under federal law, and excluding their rights under state law. The individuals who brought the case lived in New Orleans, which allowed Louisiana to return its black citizens to a position of peonage. In the Cruikshank case the Supreme Court allowed the perpetrators of a racial mass murder (the Colfax Massacre) to walk away scot free because the Court interpreted the Bill of Rights as only guaranteeing that the U.S. Congress wouldn’t abridge those rights. But if Louisiana wished to abridge them, so be it.

Step by step, the Supreme Court created the tools that allowed the South to unwind the Constitutional protections created by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, thus bringing Reconstruction to an end. Magnet doesn’t allow indignation to get in the way of his building out the story of the Court’s transgressions. His prose is mercifully free of the muse of crankdom that dooms so many attempts to explain the errant ways of the Court from the New Deal through the Warren years. A cool head makes this chapter a perfect set-up to explain Thomas’s unusual jurisprudence.

How unusual is underscored by the efforts of the liberal media to paint Thomas as “wacky”—that’s the word Nina Totenberg on NPR used in her report on Thomas entering his twenty-ninth term in fall 2019. She is echoing Yale professor Akhil Reed Amar. A professor of political science at Brooklyn College, Corey Robin, who specializes in explaining to the left what he thinks conservatives are all about, depicts Thomas in his forthcoming The Enigma of Clarence Thomas as a “black nationalist.” University of Baltimore law professor Garrett Eppsdepicts Thomas as a “megalomaniac.” Epps tells Totenberg, “Thomas alone knows the original meaning of these provisions and even Madison who wrote them can be disregarded. Now that takes a level of confidence or megalomania that I find really breathtaking.”

Such caricatures float on Thomas’s unflinching willingness to dissent from both the jurisprudence of let-sleeping-dogs-lie on the “rights” the court has invented in the past variety and also with that of the let’s-venture-where-no-law-has gone-before variety. As for the latter, when Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in his gay-marriage opinion (Obergefell, 2015) that the Constitution is “a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning” [emphasis added], he opened the door to “we-the-Supreme-Court” reading whatever it wants into the Constitution. Thomas dissented: “The Court’s decision today is at odds not only with the Constitution, but with the principles upon which our Nation was built … [T]he majority invokes our Constitution in the name of a “liberty” that the Framers would not have recognized, to the detriment of the liberty they sought to protect.”

NPR follows in the tracks of the New York Times, which has for years on end run stories derogating Thomas, often in the spirit of satirizing him. A recent article by Adam Liptak ran under the headline “Precedent, Meet Clarence Thomas. You May Not Get Along.” Thomas has for close to three decades been the target of liberal ire. Most observers back in 1991 generally concluded that Anita Hill perjured herself in her attacks on Thomas, but in the course of time incessant repetition of Hill’s accusations without mention of the evidence that she lied has turned Hill into a liberal monument of truthfulness and Thomas into a sexist scoundrel for those unwilling to consult the historical facts.

Magnet makes brisk work of the false accusations. His real quarry in this book is his chapter, “Originalism in Action,” in which he paces out Thomas’s opinions over the years showing the Justice’s growing readiness to cast precedent aside in favor of the literal meaning of the Constitution. Magnet touches down for instance on a Thomas dissent in 1999 in the case Chicago v. Morales, in which the Court “struck down a democratically enacted city ordinance imposing small fines or short jail terms on criminal street gang members loitering in public places.” The Court decided this was a “vague and arbitrary” restriction on the personal liberties of thugs. In Supreme Court–speak this was a matter of “substantive due process,” but as Thomas saw it, “police power” is meant to maintain order and prevent crime. The Court’s action rested on a precedent, for sure, but an awful one (Papchristou v. City of Jackson, 1972) in which the court rescued some thieves and drug dealers from loitering charges. Thomas will have none of this. His dissent in Morales hit hard at the Court’s willingness to abandon “our most vulnerable citizens” to the depredations of street criminals. And it was one more step towards Thomas’s disenchantment with the Court’s reliance on precedent.

Magnet’s account of how Thomas’s disenchantment matured is a tour-de-force and in some ways a prediction for what lies ahead. Thomas’s intellectual authority is growing not just with the public but with his colleagues on the Court. It is little wonder that he causes such ire among progressives. He threatens the very core of their larger project, which has always depended on judge-made and administrative-agency–made law. In a final chapter, “A Free Man,” Magnet recounts Thomas’s rejection by the Civil Rights establishment and his reciprocating disdain for those who elevate victimhood as their perpetual calling. “A free man” is an apt label. Thomas may be one of the freest men in America, a man free to pursue justice, unencumbered by the ideological straitjackets that others cheerfully squeeze themselves into.

The education of Clarence Thomas is not just the education he received but the education he now gives Americans on what our freedom should look like and how we can rescue it from those who are determined to take it away. What Thomas teaches is the rule of law as our Founders conceived it—laws that we make for ourselves through our representatives, rather than those imposed by our black-robed judicial betters.

Peter Wood is president of the National Association of Scholars.