Myron Magnet

Spring 2019

His brains and bonhomie forged a band of Federalist brethren.

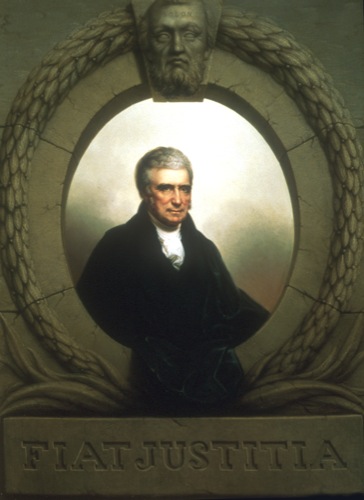

Most serious American readers know National Review columnist and National Humanities Medal laureate Richard Brookhiser as the author of a shelf of elegantly crafted biographies of our nation’s Founding Fathers, from George Washington and Alexander Hamilton up to our re-founder, Abraham Lincoln. Those crisp, pleasurable volumes rest on the assumption that these were very great men who created (or re-created) something rare in human history: a self-governing republic whose growing freedom and prosperity validated the vision they strove so hard and sacrificed so much to make real. It’s fitting that the most recent of Brookhiser’s exemplary works is John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court, for it was Marshall—a junior member of the Founding Fathers, so to speak—who made the Court a formidable bastion of the nation’s founding governmental principles, shielding them from attacks by demagogically inclined presidents from Jefferson to Jackson, until his death in 1835.

It takes all a biographer’s skills to write Marshall’s life, for he left no diaries and few letters or speeches. One must intuit the man’s character from bits and pieces of his own writings, his weighty but wooden biography of George Washington, his judicial opinions, and his contemporaries’ descriptions of him. From these gleanings, however, like Napoleon’s chef after the Battle of Marengo, Brookhiser concocts a rich and nourishing dish.

Born in backwoods Virginia in 1755, Marshall all his life kept a rural simplicity of manner and dress that once misled a Richmond citizen to think him a porter and ask him to carry a turkey home from the market, which the chief justice cheerfully did, refusing a tip for his efforts. Gregarious, athletic, and full of jokes, Marshall in his thirties was the life of the Quoits Club, a select Richmond group dedicated to weekly bibulous good fellowship and a horseshoe-like game played with metal rings, activities at which Marshall excelled. During one barroom game of inventing rhymes on assigned words, he drew “paradox” and, glancing at a knot of bourbon-drinking Kentuckians, promptly declaimed:

In the Blue Grass region,

A paradox was born.

The corn was full of kernels,

And the colonels full of corn.

“In his youth, he gamed, bet, and drank,” a temperate congressman grumbled; yet in old age, the legislator had to drive uphill in his gig, “while the old chief justice walks.”

Service in Washington’s army during the Revolution left Marshall with veneration for his commander in chief—“the greatest Man on earth,” he thought. Like most of his fellow officers, he came away from the war with the beliefs, born from the bone-chilling, stomach-gnawing privation of icy winter quarters, that became the core principles of Federalism once the Constitution was ratified—including by the Virginia ratifying convention, where Marshall played a key role. For its own preservation, the United States needed to be a real union, not a confederation of states, the Federalists held, with a central government powerful enough to fight a war and fund it, without inflicting superfluous suffering on its soldiers.

Marshall’s father, intending him for a lawyer, had given him a copy of Blackstone’s standard law text of the era, which the young man studied on his own. During one army furlough, now-Captain Marshall attended the William and Mary lectures of famed Virginia lawyer George Wythe, at the end of which he received his law license signed by his cousin, Governor Thomas Jefferson.

Interwoven with Marshall’s joking and playfulness was a strand of poetic sensitivity. Above all, he loved the greatest Augustan, Alexander Pope, and in childhood had memorized his classic “Essay on Man.” That combination of fun and poetry won the heart of high-spirited, teenaged Mary Ambler, nicknamed Polly, whom he courted during that same furlough and married in 1783. But the death of their second child at five days in 1786, followed by a miscarriage three months later, extinguished Polly’s sparkle. She slid into depression and shunned company ever after, though the bond between husband and wife never slackened. On Christmas Eve, 1831, the day before she died, Polly handed Marshall the locket he had given her to hold a lock of hair she had sent him 50 years earlier. It was around his neck when he died four years later.

In the 1780s and 1790s, Marshall juggled careers in law and government, working in his cousin Edmund Randolph’s Richmond law office before taking over his practice as lawyer to Virginia’s grandees, from George Washington on down, after Randolph’s election as governor. Meantime, his two stints in the Virginia legislature gave him an unsettling glimpse into how determined the state was to shield its citizens from the wartime debt obligations reaffirmed by the treaty that ended the Revolution, as well as by Chief Justice John Jay’s subsequent 1795 treaty reasserting those commitments—an affront both to the central government’s authority and to the sanctity of contract.

If his Federalist beliefs needed further hardening, the French revolutionary government toughened them twice over. In public mob rallies, its first ambassador to the United States appealed to the American citizenry to overturn President Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation, to the rapture of America’s newly forming, demotic Democratic Republican party, which only increased Marshall’s horror at the flaunting of federal authority. And when he traveled to Paris in President John Adams’s three-man delegation to negotiate an end to French revolutionary depredations on American shipping, only to be met with demands for a hefty bribe even to discuss the matter, his disgust with the revolutionaries, whose supposedly pure principles threw the American Democratic Republicans—with Thomas Jefferson at their head—into raptures, was complete. The delegation’s indignant refusal to the French diplomats went down in history in a slightly gussied-up form: “Millions for defense, not one cent for tribute.”

Following a stint in Congress, Marshall became Adams’s secretary of state, his main accomplishment being, Brookhiser writes, a plan that ultimately solved the long-festering wartime debt problem—as well as running the (limited) government during the irascible and unpredictable Adams’s many long absences from Washington at his home in Massachusetts. When the estimable John Jay (our most underrated Founding Father, I argue in The Founders at Home) declined Adams’s invitation to return as chief justice to replace the retiring Oliver Ellsworth, objecting that the Court lacked “energy, weight, and dignity,” Adams turned irritably to Marshall, who had delivered Jay’s response, to ask who else he could appoint before his successor took office—his Republican successor, as the Democratic Republicans were then called before they became the Democrats. “I replied that I could not tell,” Marshall recalled. “After a few minutes’ hesitation, he said, ‘I believe I must nominate you.’ ” And in this almost accidental way, Marshall began his transformative 34-year reign as chief justice, still the longest tenure in that office.

How Marshall invested the Court with the energy, weight, and dignity it formerly lacked, and how he used it to protect the Federalist legacy during the 30 years of his chief justiceship when Federalism’s opponents held the presidency, is the heart of Brookhiser’s absorbing book. Marshall began by forging the justices, all Federalists, into as convivial a fellowship as the Quoits Club, with his wit, kindness, and copious quantities of good Madeira. It helped that, as the Court met only periodically and the justices didn’t live in Washington, they lodged together in the same boardinghouse during sessions, so their discussions could go on informally over dinner and into the night. The fiction was that they drank only when it was raining, and the most junior judge was charged with looking out the window to check. If he reported fair weather, Marshall would comment, “Our jurisdiction extends over so large a territory . . . that it must be raining somewhere.” The cork would pop, and the wine and conversation flow.

But it wasn’t all in fun. The point was that the Court developed such strong cohesion, and the chief justice such moral sway over his brethren, that almost all decisions the Court issued for the next two decades were unanimous and read from the bench by Marshall, which gave them an oracular authority.

Moreover, one of the first of those decisions, Marbury v. Madison, explicitly asserted the authority of the Court as a branch of government coequal with the others. In the lame-duck flurry of the outgoing Adams administration, Congress authorized a flock of new judicial offices to fatten Federalist patronage and preserve Federalist power. These included commissions as justices of the peace, duly confirmed by the Senate, signed by Adams, sealed, and—here was the slip-up—not all of them got delivered in the rush, including one appointing William Marbury a District of Columbia justice of the peace. When newly elected President Jefferson took office in 1801, he promptly had the new Congress rescind some of the new judgeships, limiting the power grab, and he forbade delivery of the commissions already signed, sealed, but sitting undelivered on a State Department desk. Marbury asked newly minted Secretary of State James Madison for his commission, got the runaround, and asked the Supreme Court to order Madison to hand over the document, without which the administration deemed his appointment void.

Not until 1803 did the Court rule, with Marshall speaking for his unanimous colleagues. Yes, “when a commission has been signed by the president, the appointment is made,” so Marbury has a right to his office. And yes, he has a right to seek legal redress, for the U.S. government wouldn’t be “a government of laws, and not of men . . . , if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right.” But was the Supreme Court the proper venue for that remedy? According to the 1798 Judiciary Act, it was—but not according to Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, which assigns the jurisdiction of a case like this, involving such an officer as James Madison, to a lower court. Since when “two laws conflict with each other,” Marshall wrote, “[i]t is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is,” the offending section of the Judiciary Act, therefore, like “any law repugnant to the Constitution[,] is void.” Chief Justice Jay hadn’t hesitated to overturn state laws as unconstitutional, and theorists beginning with Alexander Hamilton had asserted the Supreme Court’s right to do the same to federal laws. And now Marshall had done so, in a way that proclaimed the Court’s power while avoiding a direct showdown with the incensed President Jefferson. Marbury no longer cared enough to sue for his commission in the proper lower court.

One of the several ways in which the Marshall Court advanced the Federalist, Hamiltonian vision of America as a unified commercial republic was its insistence on the sanctity of contract, starting in 1810 with Fletcher v. Peck. The outrage that had greeted the sale, for a derisory penny and a half each, of 35 million wilderness Georgia acres inhabited by Creeks and other Indians to land speculators in 1795 by shamelessly bribed state politicians sparked a newly elected legislature to pass a Repeal Act the next year, undoing the sale. Not so fast, cried the buyers of the land from the original corrupt wheeler-dealers in hopes of flipping it for big profits. When they asked Alexander Hamilton himself for a legal opinion, he replied that the land was theirs, because Georgia’s Repeal Act violated Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution, which bars states from “impairing the obligation of contracts.” When a case involving this so-called Yazoo tract reached the Supreme Court, after years of political to-ing and fro-ing, Marshall came to the same conclusion. Whatever chicanery might have taken place in the past was beyond the Court’s power to assess or redress. The only guide the Constitution could give is that a deal is a deal.

So, too, with Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, which alumnus Daniel Webster argued for the college. When Federalist-leaning Dartmouth’s trustees lost confidence in President John Wheelock and fired him, Wheelock asked the Republican governor of New Hampshire to help. He helped indeed, pressing the Republican legislature to set a Republican-leaning board of overseers over the instantly redundant trustees. The overseers promptly rehired Wheelock, and the demoted trustees sued Wheelock’s deputy, William Woodward, to have their charter, seal, and college back. An appeals court ruled that, as a public corporation involved in so public a concern as education, Dartmouth was of course subject to state control, so Wheelock’s reappointment stood.

In an 1819 decision, the Supreme Court disagreed. The college’s charter, which the Constitution’s contract clause protects, had granted its trustees the right to choose their successors, and the state of New Hampshire, by supplanting the will of the donors with its own will, had invaded that right in appointing the overseers. Moreover, the fact that the college was a public corporation emphatically did not give the state any additional rights over it, because a corporation is an artificial, immortal entity that keeps its contract rights eternally. This business-friendly decision certainly didn’t hurt the case of corporations. By 1830, 1,900 flourished in New England alone.

In two key decisions, the Marshall Court unequivocally asserted the supremacy of the federal government over the states in matters affecting the whole union, particularly when issues that made the nation a single, barrier-free trading zone were at stake. This idea grated on Republicans, jealous of state power and suspicious of finance and manufacturing. From the moment that Hamilton first proposed a national bank in 1790, Jefferson and Madison had objected that creating one exceeded the central government’s constitutional authority. But after the bank’s charter expired in 1811, Madison, who believed that “experience is the oracle of truth,” found how sorely he needed such an institution when, as president, he was reduced to financing the War of 1812 from hand to mouth, so to speak. So in 1816, Congress established a second Bank of the United States. As a prearranged test of the new institution’s constitutionality, Maryland charged and convicted James McCulloch, cashier of the national bank’s Baltimore branch, for disbursing funds without paying the state’s long-established tax on out-of-state banks. In 1819, as planned, McCulloch appealed to the Supreme Court.

Let’s start with basics, Marshall began his opinion for the Court in McCullough v. Maryland: the Constitution forged the U.S. into a single, indivisible unity. It did not create a league or confederation among the states, such as the Articles of Confederation had ordained, nor did the state governments form it. Instead, in ratifying the Constitution in their state conventions, the people of the United States created a union, whose government “is, emphatically and truly, a government of the people. In form and in substance, it emanates from them. Its powers are granted by them, and are to be exercised directly on them, and for their benefit.” These words echoed ever more pithily down the ages, Brookhiser observes, first in Daniel Webster’s 1830 rejoinder to fellow senator Robert Hayne, that the federal government is “the people’s government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people,” and then in Lincoln’s vow at Gettysburg that “government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from this earth.”

This government, “though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action,” Marshall continued. While the framers intentionally limited federal powers, they did not specify down to every jot and tittle what those powers might require for their exercise. After all, Marshall remarked, “We must never forget it is a constitution we are expounding,” not a multivolume legal code. Suffice it to say that the Constitution explicitly allows the central government the necessary and proper means to carry out its enumerated powers—and necessary means “needful,” “requisite,” “essential,” “conducive to” achieving the legitimate ends, and these include establishing a national bank—as Hamilton had argued so irrefutably three decades earlier, and as Madison painfully discovered.

Can a state tax such a national institution? Since the aim of the Constitution’s supremacy clause is “to remove all obstacles to its action within its own sphere”—and since, as Daniel Webster, arguing for McCulloch, had noted, the “power to tax involves the power to destroy”—then obviously no state government can have a power that could destroy a power granted the central government by the framers. The tax, therefore, is as unconstitutional as the bank is constitutional.

The second of this pair of federal supremacy cases, Gibbons v. Ogden, is a landmark of Supreme Court jurisprudence and an inflection point in American economic history. It also boasts a cast of famous players in cameo roles, in addition to lead actors Marshall and Daniel Webster, Gibbons’s lawyer. The case began with the pioneering steamboat launched on the Hudson River in 1807 by entrepreneur Robert Fulton and his financier, former congressman and diplomat Robert R. Livingston. Not the paddle-wheeler itself, but rather the monopoly that Livingston held from the state legislature to run it commercially in New York waters, was at issue here.

Other Fulton and Livingston vessels followed, and their success naturally attracted competitors. New York’s top court, with famed Chancellor James Kent presiding, swatted away an in-state firm plying in-state waters: the Constitution, to which the new entrants had appealed, had nothing to say about intrastate commerce. But after Fulton and Livingston died, and former New Jersey governor Aaron Ogden took over their firm and monopoly, a new competitor, Thomas Gibbons, started running steamers between New Jersey and New York. The monopoly fought back, though upstart Gibbons’s young business manager and skipper, Cornelius Vanderbilt, evaded its process servers as long as he could outwit them. But at last, the case ended up before Chancellor Kent, who again backed the monopoly. So newcomer Gibbons appealed to the Supreme Court.

Webster’s February 1824 argument on his behalf was characteristically grandiloquent. Of course, the Constitution’s commerce clause regulates such interstate commerce as that between New Jersey and New York—“[n]ot the commerce of the several states, respectively, but the commerce of the United States,” which is “an unit,” as “described in the flag which waves over it, E PLURIBUS UNUM.”

Marshall began his opinion with a formula for interpreting the Constitution that is identical to Justice Clarence Thomas’s originalism. The words mean what the framers and ratifiers thought they meant, he said. “The enlightened patriots who framed our Constitution, and the people who adopted it, must be understood to have employed words in their natural sense, and to have intended what they have said.” When the Constitution gave Congress the power to regulate commerce among the several states, it had in mind interstate buying, selling, and transporting goods, including upon the “deep streams which penetrate our country in every direction [and] pass through the interior of almost every state in the Union.” That power does not extend to “commerce which is completely internal” in a single state and “does not extend to, or affect other states”—a dictum that would have derailed the New Deal.

But having stated such grand principles, Marshall then based his opinion on narrower grounds, as the Court often does. Gibbons had a federal coasting license, protecting American navigators from foreign competition—and therefore, his lawyers contended, from state laws. “A license to do any particular thing is a permission or authority to do that thing,” Marshall ruled—stretching the point—so New York State had no business to interfere. Brookhiser notes that so narrow a ruling couldn’t be construed to apply to the interstate slave trade, so it wouldn’t stir fears of federal interference among Marshall’s fellow slave-owners. As for the steamboat trade, he notes, 12 days after Marshall read his decision, a craft from Connecticut steamed into New York Harbor, and within two years the number of steamboats serving New York had risen sevenfold, and Commodore Vanderbilt was on his way to becoming a transportation tycoon. There’s nothing like a dependable rule of law protecting free trade to boost commerce.

Marshall had claimed sweeping power for the Court in McCulloch, but, as a practical matter, how far does that power really reach? One sharp answer came in 1832. The year before, Marshall had penned an opinion in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia that had left him with regrets. He felt compelled to refuse the Cherokees’ standing to sue in the Supreme Court, because they were not—as they claimed to be, but as the Commerce Clause of Article I seemed to deny—a sovereign nation. Nevertheless, he evidently felt the injustice of a Georgia law, in accordance with President Jackson’s Indian removal policy, stripping the assimilated, Christianized, flourishing tribe of its ancestral lands and tradition of self-government in order to goad it west of the Mississippi, and he suggested in Cherokee Nation that perhaps another case with the proper parties might bring the issue before the Court once again.

That case was Worcester v. Georgia. A recent Georgia law had obliged all white men living in Indian territory within the state to get a license to do so, and when Congregationalist missionary Samuel Worcester failed to comply, he was arrested, marched 80 miles in chains to trial, and sentenced to four years’ hard labor. He appealed to the High Court in 1832, and Marshall ruled that the Constitution, and the various treaties made under its authority between Indian tribes and the United States, though they didn’t make the Cherokees a sovereign nation, nevertheless did give them a special status, placing them under federal jurisdiction and protection. Consequently, Georgia had no business making laws to govern them, including—among more important ones, implicitly—the one that required licenses of missionaries in Cherokee territory. Worcester therefore should go free.

“Well,” President Jackson drawled, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.” Worcester remained in prison, and six years later the Cherokees began their westward trudge down the Trail of Tears.

Marshall’s last major case, Barron v. Baltimore, highlighted a different limit on the Court’s power. Lumber merchant John Barron and a partner had put up $10,000 and borrowed another $15,000 to buy a wharf in Baltimore Harbor in 1815. But a city drainage and street-improvement program two years later resulted in the harbor silting up around Barron’s wharf, so that big ships could no longer use it. The partners sued the city for damages, won in the trial court, but lost when Baltimore appealed, after both men were dead. Their creditor appealed to the Supreme Court, claiming that Baltimore’s action constituted an illegal taking under the Fifth Amendment. Marshall ruled against him, noting that the first eight amendments protect citizens against federal invasions of their rights, not state or local ones. Those additional protections would have to wait for the post–Civil War Fourteenth Amendment (which, as I recount in Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution, the Supreme Court itself subverted and then distorted almost as soon as it was ratified).

Abraham Lincoln thought that the Constitution’s framers well understood that slavery was inconsistent with the principles that guided them, but, as realists practicing the art of the possible, they recognized that the Southern states would not ratify a document abolishing the vile institution, so they accepted three-fifths of a loaf rather than none. They assumed that the glaring flaw in the self-governing republic they ordained would vanish over time, as the exhaustion of the soil in the South’s tobacco states made slavery ever less profitable. But when Eli Whitney’s cotton gin made the cotton of the Deep South America’s largest and most profitable export, those dreams dissolved.

It certainly didn’t help that Andrew Jackson appointed Roger Taney as John Marshall’s successor. Taney’s 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision overturned the Missouri Compromise, declaring, on Marshall’s reasoning in Barron v. Baltimore, that the Bill of Rights applied to territories under federal jurisdiction. Therefore, under the Fifth Amendment’s protection of private property, slave Dred Scott did not cease to be property and regain his freedom by being taken into the Wisconsin Territory. As Brookhiser emphasizes, among the many citizens this decision outraged was Lincoln, who constantly attacked it over the next four years. Finally, with Taney seated behind him during his first inaugural address as president in 1861, he lambasted it again. Sure, the Court’s rulings “are entitled to very high respect.” But if “the policy of the government, upon vital questions, affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, . . . the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

That problem is vexing Americans down to this very day.

Myron Magnet, City Journal’s Editor-at-Large, is a National Humanities Medal laureate. His new book is Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution.