Montpelier Restored

I spent Presidents’ Weekend in Orange, Virginia, celebrating the inauguration of the restored Old Library at Montpelier, at which I was thrilled to be the speaker. With its breathtaking view out to the Blue Ridge 17 miles away (and uncharacteristically snow-covered that February Sunday), the serene, sun-filled, second-floor room is where James Madison began preparing throughout the spring and summer of 1786 for the Constitutional Convention that opened on May 25, 1787. Indefatigably, Madison pored over hundreds of books that his best friend and Piedmont neighbor, Thomas Jefferson (then U.S. minister in Paris), had sent him by the crateful from the shops of Europe—tomes on history and political philosophy in English, French, and Latin that Madison felt sure would provide him with clues as to why earlier democracies and confederations had failed, so that he could outline a plan for an unprecedented, and unprecedentedly successful, large-scale democratic republic. He summarized his conclusions in a handwritten pamphlet, which he consulted often during the Convention’s debates, before mining it for three of the 27 Federalist Papers that he wrote. We revere Madison, properly, as the Father of the Constitution; it’s in this room, a sacred shrine of American liberty, that the shape of that immortal document first came into focus.

It was thrilling, too, to see the progress the Montpelier Foundation, now under the dynamic leadership of Kat Imhoff, has made on the restoration of Montpelier’s interior since the last time I saw the house in 2010. The entire project has been Herculean, given the mansion’s confusing evolution. Madison’s father, a rich, third-generation Virginia planter, had built the core of the house in the 1760s. A two-story, five-bay Georgian brick structure—that is, it had two windows on each side of its central front door—it was then Orange County’s biggest residence, commanding 5,000 acres of lush Piedmont farmland. When Madison married Dolley Payne Todd and temporarily retired from government in 1797, he added what was in effect an attached townhouse, three bays wide, to his parents’ residence. The result was a still-symmetrical eight-bay house, with three pairs of windows punctuated by two doorways. A new columned and pedimented portico embraced the two doorways and emphasized the house’s symmetry further.

Starting in 1809, during the first of his two presidential terms, Madison began building one-story wings on either side of the house, surmounted by roof terraces enclosed by Chinese Chippendale railings, all designed with advice from his friends Jefferson, Capitol architect William Thornton, and White House interior designer Benjamin Henry Latrobe. One wing housed a grand library; the other provided new quarters for his widowed mother, who lived with him and Dolley until she died at 97 in 1829. An imposing pedimented and fan-lit central doorway, with a new demi-lune window in the portico’s pediment directly above, provided a stately presidential focal point for the perfectly balanced mansion.

Of course big changes took place in the interior as well over that half-century. Madison’s 1797 addition had a first floor entirely separate from his parents’, in order to give him and his little household—Dolley, Dolley’s young son from her first marriage, and Dolley’s youngest sister—some privacy, and perhaps to spare the elder Madisons some childhood commotion as well. The second floor, reached by separate staircases for each generation, was all interconnected, however. Madison’s presidential expansion of the house broke down the first-floor barrier, created a splendid drawing room suitable for presidential receptions, and added a sumptuous chimneypiece to the dining room. Adorning the dinner table, which could seat 18, was a service of Vieux Paris pocelain, bought from the Nast factory in 1806.

This complex evolution is easy to relate, but it took years of painstaking effort by restorers to reconstruct it. Why? Because in 1901, gunpowder and chemical magnate William du Pont, Sr., bought the house, already repeatedly altered from the moment an impoverished and widowed Dolley had to sell it in 1844, and he swallowed up the remains of Madison’s mansion in a gargantuan enlargement from 22 rooms to 55, smashing through chimney-pieces, paneling, and other impediments in the process. His daughter Marion turned the house into the hub of a thoroughbred horse-breeding and horse-racing enterprise, installed an art-deco living room, more garish than stylish, in Mother Madison’s quarters, and dug out the cellar to build a gym for her husband, cowboy-movie-idol and Cary Grant’s longtime close friend and California housemate, Randolph Scott. The result was a hulking pink-stucco bunker with a metal roof. As a stab at comely proportion, the du Ponts lengthened the portico columns to the ground; they had originally sprung from the top of the stairs. It’s only justice to add that Mrs. Scott left money in her will, and instructions to her heirs, that helped put Montpelier right.

I first saw the house in 2007, when restorers had demolished most of the du Pont additions, chipped off the stucco to reveal the warm rose-colored handmade brick of the original house, recreated the early-nineteenth-century presidential floor plan, and removed the waterlogged du Pont plaster from the interior, leaving only the original laths, hand-cut between the 1760s and 1810 or ’12, when Madison’s final renovation was complete. Walking through Montpelier then was an eerie experience, since I could see between the laths from room to room to room, as if I were in a ghost house. By then, restorers had moved Marion duPont Scott’s art deco extravaganza to a visitor center.

When I returned three years later, restoration chief John Jeanes showed me how his crew had plastered the interior with the original lime, sand, and horsehair formula, and re-roofed the house with 30,000 hand-carved old-growth cypress shingles, copied from some original cedar ones found in the attic—but so much tougher that the new roof, Jeanes predicted, would last 100 years. He showed me too how careful removal of layers of paint on the sides of the window frames had revealed the outlines of the original chair rails, so his team could reproduce them precisely. One of the second-rate old-master paintings that had adorned the drawing room hung in its original position, and copies of the others, along with portraits of Madison’s Founding Father colleagues, hung where the originals had been. Some pieces of the old house had turned up during the restoration—a hearthstone that had fallen into the basement, for instance, a doorway that the duPonts had relocated—but the few bits of furniture in the rooms only punctuated their emptiness, since Dolley’s wastrel son, a drunkard and gambler whom Madison once bailed out of debtors’ prison, had sold off most things of value after his stepfather’s death.

The intervening four years have produced a miraculous change. Furniture said to have belonged to the Madisons has poured in from eager donors, and many pieces, after rigorous vetting, have turned out to be genuine. Museums have loaned Montpelier items known to have come from the house. Every furnished room displays original Madison pieces, from the two sideboards in the dining room to a tea table in Mother Madison’s sitting room that she probably acquired even before she and her husband built Montpelier. An original Montpelier chimneypiece turned up in a nearby farmhouse and is now back where it belongs.

From poring over documents, restorers had a fairly detailed idea of what was in the house during the Madisons’ period, and, in cases where original pieces had vanished completely, they often could replace them with almost identical ones. Madison had bought a square piano from a Philadelphia maker in 1794, for example, and Montpelier now has one made by the same firm that very year. The house displays an ivory chess set identical to the original one, of which only a few pawns turned up in a Montpelier rubbish heap, and a mahogany case of plaster portrait-medallions of philosophers, made by the same Italian craftsman who made the Madisons’ now-lost set, stands near it in the drawing room. The Madisons owned some painted Louis XVI drawing-room chairs that they had probably bought when George Washington auctioned off some of his presidential furniture on his retirement to Mount Vernon at the end of his second term. Washington had bought the originals, made by a Parisian cabinet maker named Lelarge, from a departing French ambassador, and he had a Philadelphia craftsman make copies to enlarge the set. Six of the Madisons’ chairs still exist in various collections, including one at Montpelier. Some are French, one complete with Lelarge’s stamp; some are President Washington’s American copies. The Montpelier Foundation has recently bought ten almost identical ones, stamped Lelarge, to adorn the drawing room.

During the restoration, a workman on a tall ladder found a bit of red flocked wallpaper stuck to the top of a drawing-room window frame, though the thumbnail-sized scrap was too small for curators to make out what the original pattern was. Reasonably, they chose a red-flocked pattern popular in the early nineteenth century. A two-century-old mouse’s nest found inside one wall contained a scrap of a letter in Madison’s hand and some threads of crimson silk—evidence for restorers to surmise that this was most likely the crimson of the silk damask that Dolley had ordered from France in 1816 for the curtains and upholstery of Montpelier’s drawing room, now reproduced in fabric and color, if not in pattern. Tack holes in the drawing-room and dining-room window frames suggested how the curtains originally hung; but no shred of evidence remains for the pattern of the dining-room curtains or wallpaper, though it’s hard to imagine that the flamboyance the restorers chose would have displeased the exuberant Dolley.

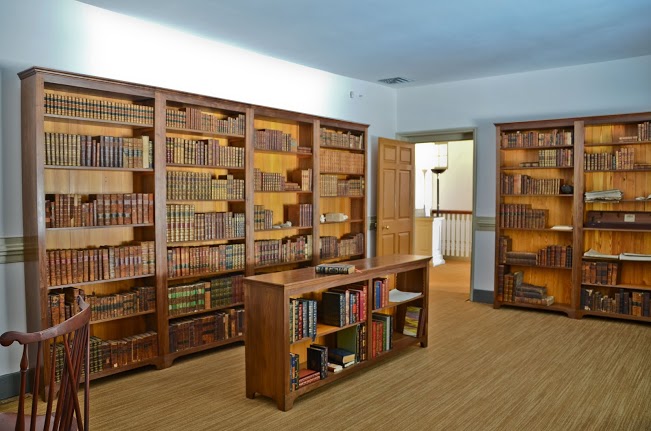

And finally, the Old Library—the goal of my pilgrimage—has got some 900 of its 4,000-odd books back. They’re not Madison’s originals, but they are the same works, largely in the same editions he owned—from Cicero’s writings and Bacon’s essays to Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. “The past should enlighten us on the future,” Madison once wrote: “knowledge of history is no more than anticipated experience.” In these volumes is enshrined some of the knowledge that informed our Constitution. The ink splatters Madison made while taking notes on them—original splatters, not copies—still adorn the heart-pine floorboards of the hushed room, where Madison listened to such great effect to the eloquent voices of our civilization’s sages.

Photographs courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation