Giving Thanks in the Land of the Free

Americans have long treasured their right to worship as they choose.

By

MYRON MAGNET

Wall Street Journal, Nov. 26, 2013 7:18 p.m. ET

In the fall of 1621, some 50 of the Puritans who had left the Old World in search of religious freedom sat down in their tiny thatched hamlet of Plymouth with their Wampanoag neighbors to feast on turkey, venison, corn and cod. They also gave thanks for surviving their first terrible New England winter, whose cold and privation had carried off half their community.

Continual waves of pilgrims fleeing religious persecution would follow them across the sea. Their sense of providential escape from foreign oppression stayed vividly alive in the American memory, and ultimately helped guide the Founding Fathers to make a revolution and fashion a new kind of government.

Hard as it is to believe at this distance of time, British law once jailed non-Anglican Protestants like the Pilgrims for worshiping as they chose. The law also barred them from the universities and public office. Thousands of Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers and others left their native land, bringing to the New World their Dissenting tradition of self-government, individualism and personal responsibility. They had long run their own congregations, hired and fired their own ministers, read the Bible and freely judged its meaning for themselves. They believed that each individual has a direct relation to God independent of, and higher than, any worldly authority.

As late as the 1750s, Constitution-signer William Livingston was still reminding readers of his influential magazine, The Independent Reflector, how “the countless Sufferings of your pious Predecessors for Liberty of Conscience, and the Right of private Judgment” drove them “to this country, then a dreary Waste and barren Desert.”

Decades later, Chief Justice John Jay wrote a gripping account of how his grandfather, a French Protestant, had returned home from a trading voyage abroad in 1685 to find his family and neighbors gone, their church destroyed. While he had been away, Louis XIV of France revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had extended religious toleration and civil rights to Protestants for almost a century. Jay’s grandfather was lucky to be able to sneak aboard one of his ships and, like many others, sail away to freedom in the New World.

With this long history, Americans have had an almost physical thirst for liberty, as people do who truly know its opposite, like Eastern Europeans who once lived under communist tyranny. Long before Emma Lazarus wrote her Statue of Liberty verses about the huddled masses yearning to breathe free, George Washington noted that for “the poor, the needy, & the oppressed of the Earth,” America was already “the second Land of promise”—the Promised Land. It offered, said James Madison, “an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion.”

That thirst for liberty led the Founders to revolt when they thought that George III was squeezing upon them the tyranny that had crushed their forebears. It also led them to hedge their new government with every safeguard to keep them free.

To protect life, liberty and property from what they called the depravity of human nature—from man’s innate capacity for inhumanity to others—the Founders knew they needed some kind of government armed with power. But since the officials who wield such power have the same fallen human nature as everyone else, who can be sure that they won’t use it to oppress others? Who can guarantee that imperfect men wouldn’t turn even the democratic republic the Founders were creating into what Continental Congressman Richard Henry Lee called an elective despotism?

The Constitution they wrote in the summer of 1787 explicitly limited government’s powers to what they deemed absolutely essential. They divided and subdivided power, and they made each branch of government a watchdog over the others. But they also recognized that constitutions are only what they called “parchment barriers,” easily breached if demagogues subvert the “spirit and letter” of the document.

In the first State of the Union address, George Washington stressed that the ultimate safeguard against such a danger is a special kind of culture, one that nurtures self-reliance and a love of liberty. “The security of a free Constitution,” he said, depends on “teaching the people themselves to know and to value their own rights; to discern and provide against invasions of them.”

If citizens start to take liberty for granted, he said, the spirit that gives life to the Constitution will flicker out, for “no mound of parchm[en]t can be so formed as to stand against the sweeping torrent of boundless ambition on the one side, aided by the sapping current of corrupted morals on the other.”

It’s that culture of liberty we nourish by recalling that our forebears came to these shores in search of freedom—and by giving thanks that they found it.

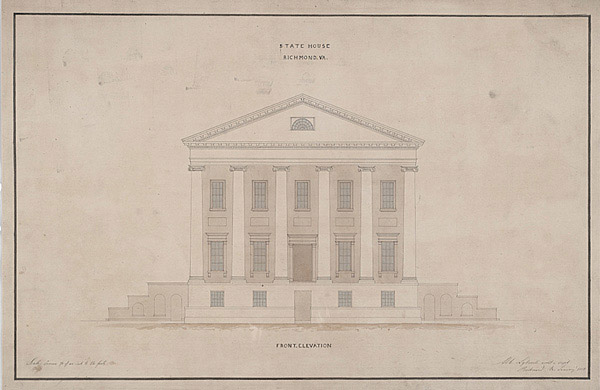

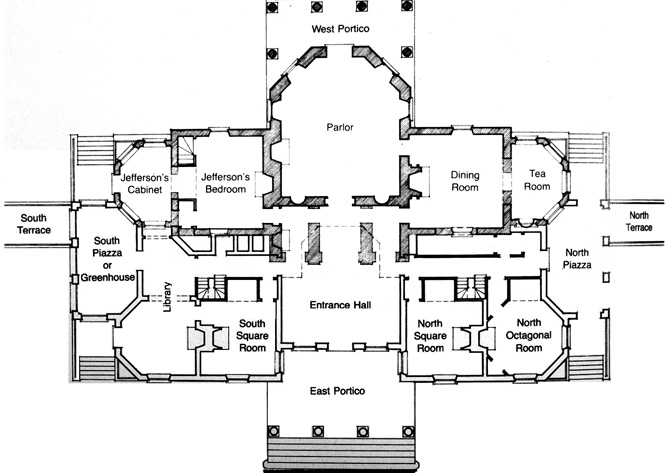

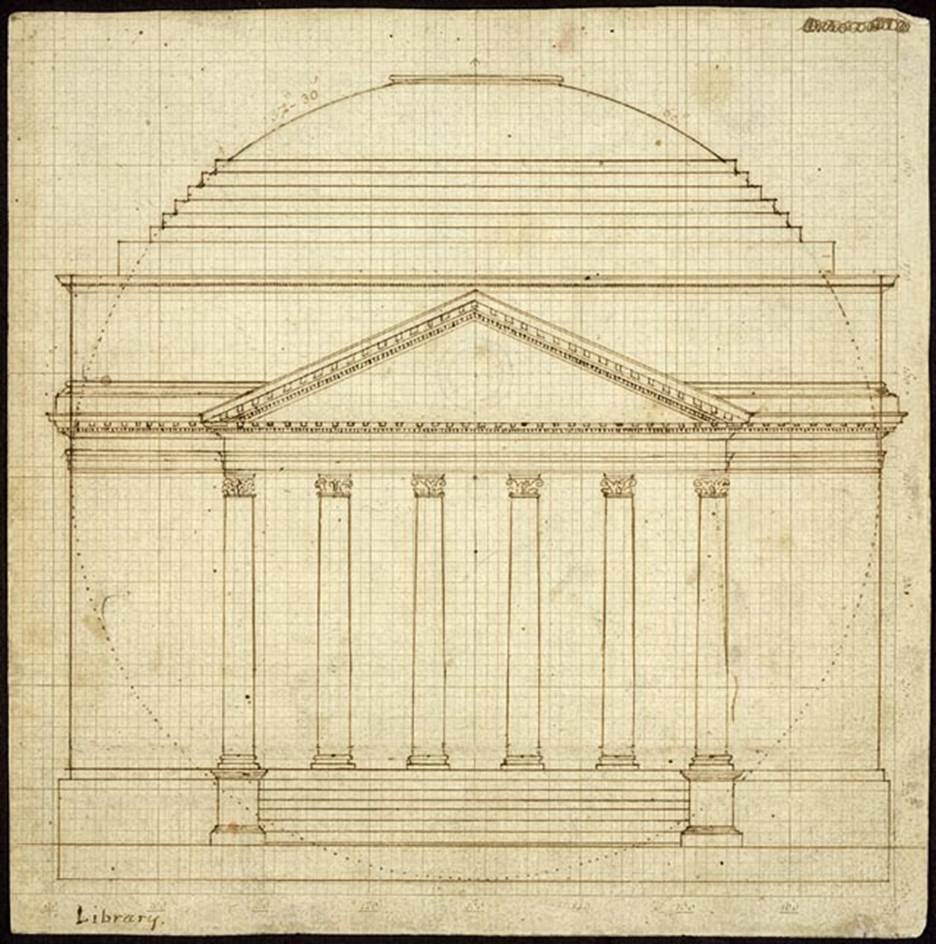

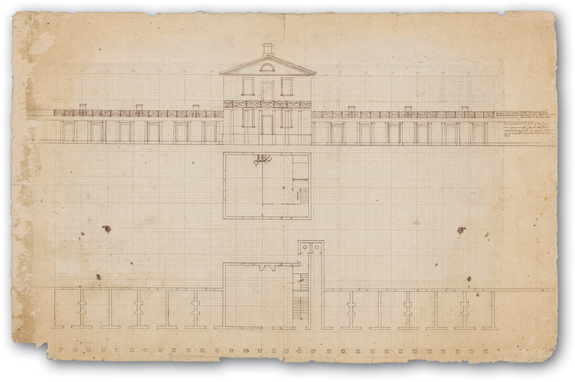

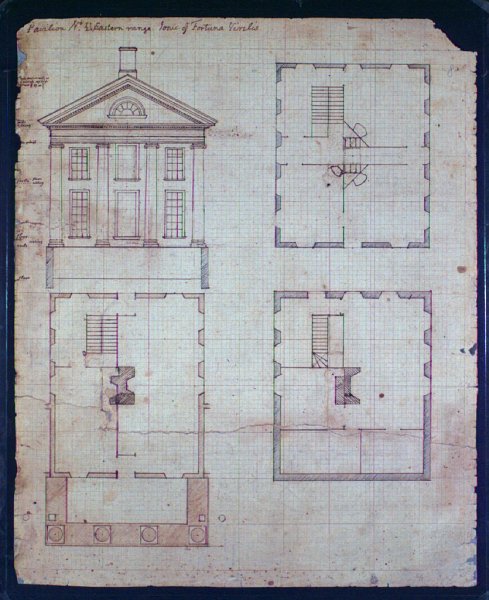

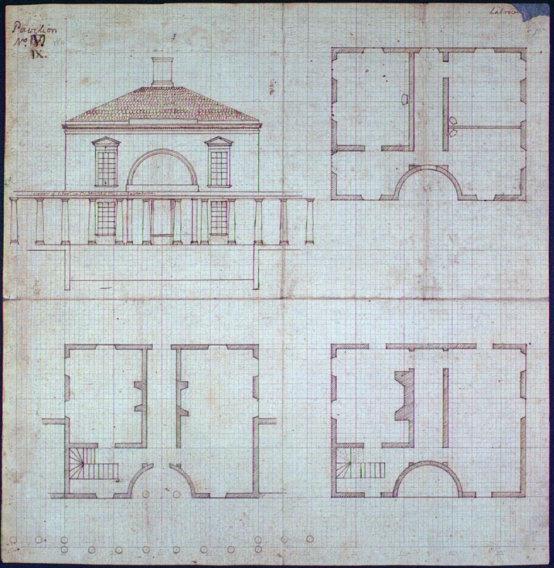

Mr. Magnet is editor-at-large of the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal. His new book is “The Founders at Home: The Building of America, 1735-1817” (Norton).

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304655104579165800736157752?mod=WSJ_Opinion_LEFTTopOpinion