A Bus Too Far

Summer 2025

MYRON MAGNET

Beneath the righteous, reforming passion of the civil rights era that suffuses Michelle Adams’s The Containment: Detroit, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for Racial Justice in the North, one can’t help perceiving how unexamined and sometimes simplistic the University of Michigan constitutional law professor’s fundamental assumptions are. Consequently, after closing this painstakingly argued tome, the reader almost inevitably thinks past its conclusion—pondering, beyond the particular failure of the civil rights movement that Adams laments, the radical way that movement changed American society not only for the better but also for the worse.

The Containment tells the story of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision against school busing in Milliken v. Bradley (1974), from its beginnings as a district court case in 1970 to its epilogue in the high court’s Milliken II ruling in 1977. Adams sets the stage with a fiery 1967 debate at the Detroit Board of Education about how to reform the city’s awful public schools, which had been majority black since 1963. Asking why black pupils were disproportionally failing and dropping out, Albert B. Cleage, Jr., pastor of the Shrine of the Black Madonna and an admirer of Malcolm X, highlighted white teachers and principals as the problem. They systematically destroy black kids’ “self-image and racial pride,” making them feel intellectually inferior and sapping their motivation. The last thing these kids need is more integration. What they need is community control of their schools, with black parents overseeing the hiring and firing of black teachers and vetting the curriculum, textbooks, and discipline. This prescription was part of Cleage’s larger vision of a black “nation within a nation,” in which blacks would own and patronize their own businesses, professional services, and farms, set their own goals, and forge their own culture.

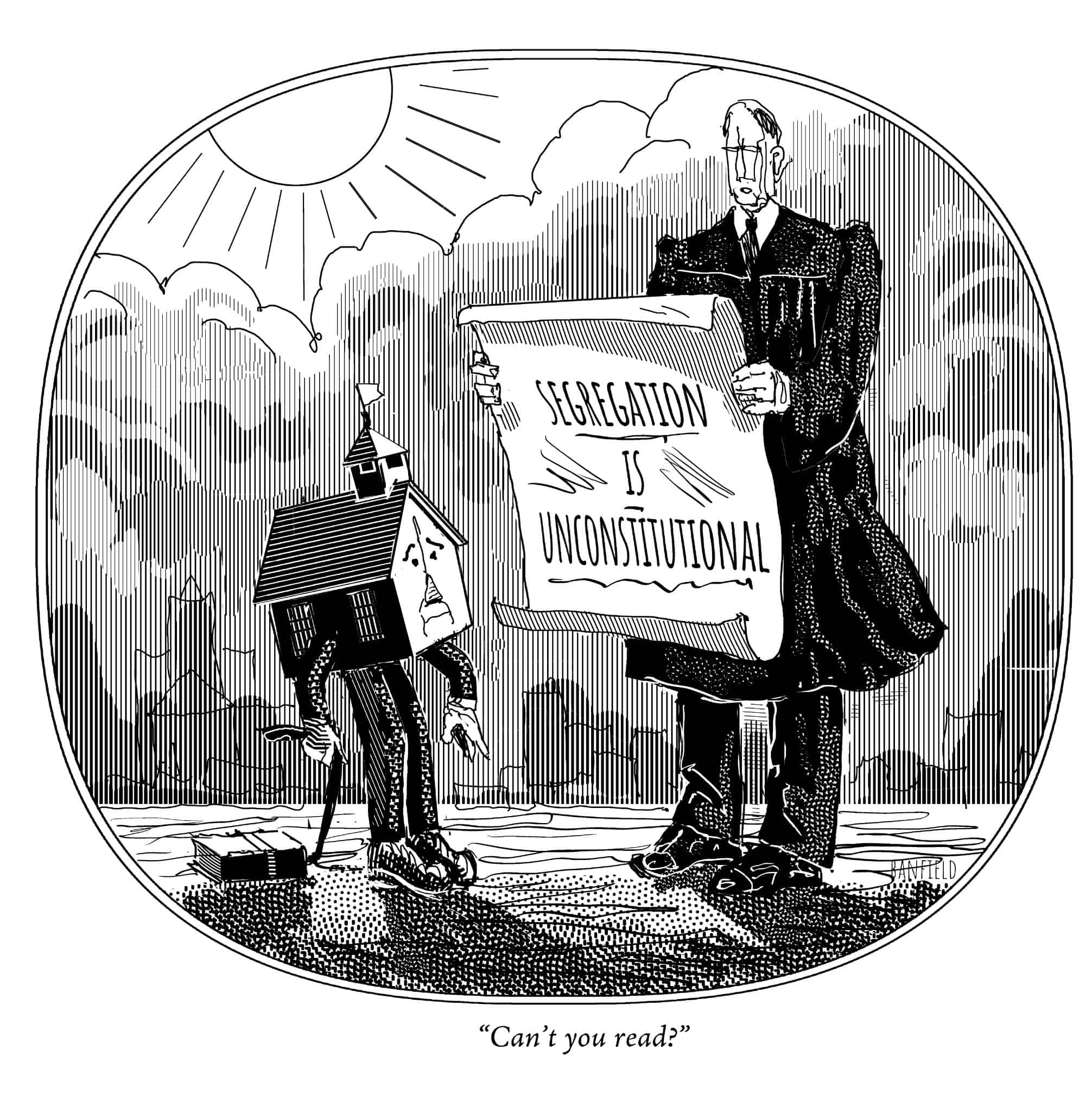

Hotly opposing Cleage’s black nationalism was the civil rights orthodoxy backed by the board’s future president, Abraham Zwerdling, a white labor lawyer and longtime National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) member. He and his liberal board allies espoused the argument underlying the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision, which held—based on psychologist Kenneth Clark’s flimsy study of black kids’ preferences for white dolls over black ones—that segregation, by separating black children from their white peers, did them deep emotional harm, generating “a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” Separate schools, therefore, were inherently, unconstitutionally unequal, and integration was the sine qua non for black educational success. Continue reading