Clarence Thomas: the Movie

Don’t miss this new documentary.

Myron Magnet

January 31, 2020

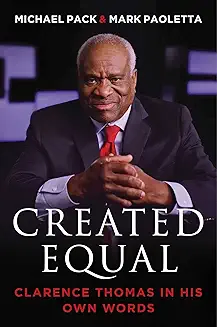

From a kerosene-lit shanty in a Georgia swamp to the Supreme Court bench is almost as meteoric a rise as from a log cabin to the White House, and if you add in overcoming segregation in the days when the KKK marched openly down Savannah’s main street, it’s closer still. Michael Pack’s riveting documentary on Justice Clarence Thomas, Created Equal—opening in theaters this week and airing on PBS in May—movingly captures the uncompromising ethic that propelled the justice’s career past so many obstacles as it distills 30 hours of interviews with Thomas and his wife, Virginia, into what feels not only like the exemplary life story of an underappreciated hero but also like a laser-focused, two-hour account of our nation’s race relations over the last 70 years. Yes, we overcame, but at a cost—of which Justice Thomas paid more than his fair share.

The film is purely biographical—Thomas’s brilliant jurisprudence plays no role here—and the justice’s somberly eloquent, slightly melancholy recounting of his saga as he faces the camera directly, dark-suited, with starched white shirt and monochromatic necktie, closely follows the style of his bestselling memoir, My Grandfather’s Son. But as Thomas tells his story, Pack shows us haunting images, over a nostalgically evocative American musical score—bluegrass guitars and banjos, jazz, and Louis Armstrong longingly singing “Moon River” (with lyrics by Savannah-born Johnny Mercer, Thomas reminds us)—that bring it all even more vividly to life than the excellent memoir does. The film clips of the mazy creeks around Thomas’s birthplace, the coastal Georgia hamlet of Pin Point—founded by freed slaves just after the Civil War—sometimes seen from above, as in the iconic shot toward the end of The African Queen, and sometimes seen as we travel along them in one of the little “bateaux” that the oystermen and crab fishers of that lush and remote outpost on the very edge of America still use, bring home how “far removed in time and space” it was from modern, urban America, as Thomas puts it.

It was a completely different world—a tiny, poor, all black community of jumbled shacks around the cinderblock workshop where the women picked the crabs and shucked the oysters that the men caught and raked. The still photos Pack found from the 1940s show you a preindustrial world so vanished that it could just as easily be the nineteenth century as the twentieth. Descended from West Africans, Thomas and his neighbors spoke a dialect called Gullah or Geechee, incomprehensible to outsiders; but when Pack shows us a film clip of a woman singing that patois as she feeds her chickens, we grasp viscerally from the creole lilt how this corner of America was a link in Britain’s triangle trade, with ships bringing enslaved Africans to the Caribbean and southern colonies, carrying the sugar north for distillation into rum, and returning to Britain to sell it.

For Thomas and his playfellows, this was a Mark Twain world of improvised games in the woods and swamps, with no such thing as a store-bought toy—until the heartbreakingly tiny, jerrybuilt shack where he lived with his mother, older sister, and little brother burned down. He came home to “just ashes and twisted tin,” he says. “Everything that you ever knew in life is just there—I mean, it’s smoldering.” Continue reading →