Books and Culture

MYRON MAGNET

The Last Founding Father

Richard Brookhiser’s new biography of Lincoln is splendid.

17 October 2014

Founders’ Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Richard Brookhiser (Basic Books, 376 pp., $27.99)

Unlike those mega-biographies that bury their subject’s chief accomplishments under 900 pages of undigested detail, Richard Brookhiser’s compact, profound, and utterly absorbing new life of Abraham Lincoln, Founders’ Son, leaps straight to the heart of the matter. With searchlight intensity, it dazzlingly illuminates the great president’s evolving views of slavery and the extraordinary speeches in which he unfolded that vision, molding the American mind on the central conflict in American history and resolving, at heroic and tragic cost to the nation and himself, the contradiction that the Founding Fathers themselves could not resolve.

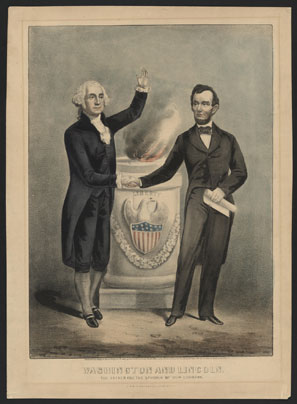

Of Lincoln’s youth, therefore, Brookhiser gives us only telling vignettes: his sense of close connection to the Founding through the Revolutionary War-veteran grandfather for whom he was named; the kindly stepmother who entered his hardscrabble life like a ray a sunshine and encouraged his love of reading and thinking, so that, after false starts as a riverboat man and a storekeeper, he could teach himself to be a lawyer by dogged solitary study; the rain-stained copy of Parson Weems’s biography of George Washington that fired his boyhood imagination with the momentous meaning of the American Founding, and that stoked (I would guess) the ambition, which he expressed almost in Washington’s very words, to “be truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem;” the passionate belief in “a man’s right to own the fruits of his own labor,” bred not only by having to work as an unpaid field hand for his dirt-farmer father but also by his father’s hiring him out to other farmers and pocketing his wages; his related belief, also conceived in servitude, and later strengthened by the Hamiltonian vision of Henry Clay, that the purpose of American liberty was, as Brookhiser puts it, “to make men—to develop the talents of individual Americans;” the melancholy, engendered by the early deaths of his mother, his sister, and his fiancée, that “dripped off him as he walked,” said his law partner; the fatalism he often expressed in the adage, “What is to be will be, and no prayers of ours can reverse the decree;” and the loveless marriage he made to Mary Todd in 1842, which left him, judges Brookhiser, with “passion to spare” for matters political.

Through what magic, then, did a one-term congressman—he served from 1847 to 1849—manage to get elected president in 1860? It was the genius of his oratory, inspired by models as diverse as Tom Paine and the Old Testament, coupled with a lifelong conviction that the Founding Fathers had struggled to create “something even more than national independence; . . . something that held out great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come.” They had fought, as Parson Weems put it, for the “GENIUS OF LIBERTY,” and their struggle, Lincoln believed, was now his charge. When we speak of wanting a politician of conviction, this is the standard we must use.

Lincoln did not start out an abolitionist. As early as 1837, he showed ambivalence on the subject. When the Illinois legislature voted to condemn abolition societies as unnecessarily provocative that year, legislator Lincoln and a colleague voted yes but entered a protest, declaring for the record “that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy.” Even so, as a campaigner for Whig candidate William Henry Harrison in the election of 1840, Lincoln, in a debate with Martin Van Buren supporter Stephen Douglas, “was not above slyly trafficking in prejudice,” Brookhiser notes, attacking Van Buren for supporting voting rights for New York State’s free blacks. But as his congressional term drew to an end in 1849, he proposed (unsuccessfully) a plan for ending slavery in the District of Columbia, and the next year, when the three-decade-long era of trying to find a compromise on the issue of slavery came to a climax with the Compromise of 1850, Lincoln knew that the choice between slavery and abolition was inevitable for the nation—and he knew that he would stand against slavery. “When the time comes my mind is made up,” he told a friend, “for I believe the slavery question can never be successfully compromised.”

The time came soon enough, with the infamous Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. In effect, the act repealed the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which, in admitting Missouri as a slave state, had barred slavery from the rest of the Louisiana Territory lying north of the 36° 30’ parallel. By the terms of the new act, however, settlers pouring into the vast, hitherto empty territories of Kansas and Nebraska, which mostly lay north of the 1820 line, could choose whether to admit or bar slavery by “popular sovereignty,” the term used by Democratic senate leader Stephen Douglas, who boasted of having “passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act myself. . . . I had the authority and power of a dictator throughout the whole controversy.”

Though what we call the Lincoln-Douglas debates occurred in their Illinois senatorial contest of 1858, the “six years from 1854 to 1860 were one long Lincoln-Douglas debate,” writes Brookhiser, as Douglas went around the state defending the act and an indignant Lincoln pursued him, rebutting his emollient arguments in a string of immortal speeches. In Peoria in October 1854, Lincoln condemned Douglas for reopening an already scabbed-over wound. “Every inch of territory we owned already had a definite settlement of the slavery question,” he observed; but thanks to Douglas, “here we are in the midst of a new slavery agitation.” Douglas wants the people of the territories to decide? Fine. But who the people are “depends on whether a Negro is not or is a man.” If he is, then isn’t it “a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself?” When a white man “governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism.”

Lincoln appealed to the authority of his beloved Founding Fathers—a subject Brookhiser, biographer of several of them, knows better than most. These great men found slavery already existing in the colonies, and to forge a new nation that the slave states would agree to join, they had to accept the evil out of necessity, not principle. They clearly knew that it was wrong, as is evident in the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, by which the Continental Congress strove to prevent slavery’s spread to unsettled territories; in the Declaration of Independence—“the sheet anchor of American republicanism,” said Lincoln, “that teaches me that ‘all men are created equal,’” including blacks, who are emphatically men; and in the Constitution itself, which accepted slavery so reluctantly that it wouldn’t even name it, Lincoln noted, “just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or cancer, which he dares not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death.” So let’s not go beyond where the Founders felt themselves forced to go. Let’s not metastasize slavery further.

In March 1857, the Supreme Court handed down what Brookhiser rightly calls “its worst decision ever” in the Dred Scott case. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote that Scott, a slave whose master had died after taking him north of the Missouri line, had no right to sue for his freedom, because blacks were not citizens and therefore had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” including the right to sue. Moreover, Taney continued, the Missouri Compromise, to which Scott appealed for his freedom, was unconstitutional. Insofar as it implied that a citizen’s slave might become a free man simply by crossing an imaginary line, it violated the Fifth Amendment, by depriving citizens of their property without due process of law.

Douglas viewed Taney’s decision with equanimity, since in his view blacks were an “inferior race”—a race with which Lincoln’s newly formed Republican Party, he sneered in a June speech in Springfield, would be happy to intermarry. Lincoln’s response was outrage. Of course the Founders who framed the Fifth Amendment didn’t mean what Taney said they did, he thundered in a Springfield speech later in June. After all, five of the states that ratified the Constitution allowed free blacks to vote on ratifying the Constitution itself. And of course the signers of the Declaration of Independence meant to include blacks in their assertion that all men are created equal. They were stating an abstract principle: “They meant to set up a standard maxim for a free society” that would block “those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism.” As for Douglas’s charge that Republicans backed intermarriage, that is silly. It doesn’t follow that, “because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. I need not have her for either.” What is not silly, though, but everlastingly true is that “in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of anyone else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.”

In accepting the Republican nomination to run against Douglas in his Senate re-election bid in June 1858, Lincoln took the logically inevitable next step in the argument. “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” he declared. “I believe the government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” Either slavery will ultimately overrun the entire nation, or the abolitionists will stop its spread and slowly push it to extinction, though not “within the term of my natural life” but perhaps “a hundred years” hence, Lincoln prophesied.

And so the Lincoln-Douglas debates were on—seven of them, as the candidates chugged by train for thousands of miles across the state, arguing the slavery issue. The Founders, Douglas asserted, were states’-rights men, “and left each state perfectly free to do as it pleased on the subject of slavery.” And their declaration that all men are created equal “had no reference either to the negro, the savage Indians, the Fejee, the Malay, or any other inferior and degraded race.” If it did, they would have freed their slaves. Lincoln riposted with his argument of necessity: “Our fathers . . . found the institution of slavery existing among us. They did not make it so, but they left it so because they knew of no way to get rid of it at that time.” But at least they tried to limit its spread, because they knew it was so wrong that slaveowner Jefferson himself, quoted Lincoln, “trembled for his country when he remembered that God was just.” But Douglas sees nothing wrong with it. “That is the real issue,” summed up Lincoln. “It is the eternal struggle between these two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world.” On a rainy November 2, Illinois electors sent Stephen Douglas back to the Senate.

For all the disarming “rube/boob persona,” as Brookhiser calls it, that the gawky, six-foot-four, ill-dressed, frontier-bred Lincoln liked to adopt—for all his self-deprecating jokes and homespun stories—the ambition that smoldered in him as a young man had now clearly burst into a sense of calling, which appeared, one cabinet member later noticed, in an “unconscious assumption of superiority.” What else would lead a one-term congressman, with no managerial experience, to run for president in 1860 against Douglas and two minor candidates on the issue of containing and ultimately ending slavery—the “question about which all true men do care?” Perhaps he was speaking for himself, as well as for the nation, when, after repeating his usual antislavery arguments in his great first campaign speech at New York’s Cooper Union that February, he closed with this peroration: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” That he surely did, with the last full measure of devotion.

On November 6, he won. Six weeks later, South Carolina seceded from the union. In his Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, the sixteenth president tried to reassure Southerners that he had neither the right nor the inclination “to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists, and he stressed that “[w]e are not enemies, but friends,” tied together by the “mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave, to every living heart.” But by then, six more slave states had seceded from the union and formed the Confederacy, so Lincoln also vowed to hold the property the government possessed there. On April 12, as he tried to resupply Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, rebel canon boomed, the fort surrendered, and the Civil War was on. By the end of May, 11 of the 34 states had joined the Confederacy, founded, said its vice president, “upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.”

Brookhiser recounts the war in two succinct chapters—fair enough, since shelves of books already exist covering every aspect of the savage conflict—and he gives a brief but useful summary of how Lincoln freed the Confederacy’s slaves by proclamation, as a wartime commander in chief, and how he completed the job by changing his proposed Thirteenth Amendment, originally stipulating that the federal government couldn’t end slavery in the slave states, to the utter abolition of the obscene institution that won final ratification in December 1865.

Brookhiser properly devotes an entire chapter to Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, which he rightly judges the greatest of his speeches—and (in my view) is perhaps the greatest speech ever made. In it, Brookhiser believes, Lincoln completed his lifelong search for a surrogate father, moving from the Founding Fathers to God the Father. To be sure, this speech, delivered on March 4, 1865, like the Gettysburg Address given some 15 months earlier, resounds with the poetry of the King James Bible, which a childhood friend of Lincoln’s sons’ remembered the president would often read after lunch in the White House, while the children played, “sometimes in his stocking feet with one long leg crossed over the other, the unshod foot slowly waving back and forth” as he kept time to the rhythm of the Elizabethan language’s stupendous music.

But if I have one disagreement with Brookhiser’s splendid book, I would think of Lincoln not as the Founders’ son but rather as the last Founding Father, shoulder to shoulder with them in greatness as he completed their work, giving the nation a “new birth of freedom” and ensuring that the government of the people, by the people, for the people, that they had instituted but could not perfect, would not perish from the earth. And in the Second Inaugural, he sounds like an Old Testament prophet, questioning God’s purposes, even quarreling with them, as he felt himself to be the instrument of accomplishing them. Yes, the war was just and necessary, but why was it lasting so long? Why did so many have to die in the flower of their youth? “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come;” Lincoln quoted, “but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” Why would God decree that offenses must come and then punish those who act according to His decree? Why would He decree slavery, then decree its removal, and decree punishment to everyone who had benefited from it, not just Southern slaveowners but every Northern broker and shipper who had profited from it, down to his children and his children’s children? We can only carry on “with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right,” said Lincoln—however dimly that may be.

After the Confederate capital of Richmond fell a month later, Lincoln wanted to see it with his own eyes, and he walked the silent streets on April 3, 1865, with a bodyguard of only ten sailors, six days before Lee surrendered. But suddenly crowds of blacks surrounded him, shouting, “Glory to God! The great Messiah! Come to free his children from bondage.” Several touched the president, as James McPherson recounts in Battle Cry of Freedom; and one old woman cried, “I know I am free, for I have seen Father Abraham and felt him.” She was right: he was one of those world-historical figures we can never account for but can only marvel at with gratitude.

Six days after the victory, Lincoln was dead. “The Almighty has His own purposes,” he had said in the Second Inaugural. But who can tell what they are?

Myron Magnet, City Journal’s editor-at-large and its editor from 1994 through 2006, is a recipient of the National Humanities Medal. His latest book is The Founders at Home.