What City Journal Wrought

An editor looks back

Autumn 2015

The “Lights Out Club” used to meet for monthly lunches in the early 1990s, my late friend Lorian Marlantes, then chief of Rockefeller Center, told me. Why the name? Because Marlantes’s fellow members—the CEOs of Consolidated Edison, a couple of big Gotham banks, and a few other firms whose core business chained them to New York—thought that soon one of them would be the man who’d turn the lights out forever on a city that was dying before their eyes, killing their companies along with it.

In those days, you didn’t need to be Nostradamus to make such a dire prediction. The evidence was everywhere—on the graffiti-scrawled buildings and mailboxes, the potholed streets, the squalor of the panhandlers, the dustbowl that had been Olmsted and Vaux’s sublime Central Park, and the pervasive stench of urine, thanks to the bums who were turning the capital of the twentieth century into a giant pissoir, with the carriage drive of Grand Central Station the urinal of the universe.

In 1983, the Mobil Oil Corporation, to show Mayor Edward Koch why it was contemplating leaving New York, videotaped the sordidness around its 42nd Street headquarters, near Grand Central. The camera caught the rotting trash, the pee-filled potholes, the degradation of the homeless hordes—some crazy and some shiftless—through which Mobil employees had to pick their way into the then-shabby, billboard-plastered station to catch trains home to their orderly suburbs, fragrant with new-mown grass. After shots of corporate headquarters located in similarly bucolic suburbs, the wordless video closed with the written question: “What do we tell our employees?”

Mobil’s answer, in 1987, was to move to Fairfax, Virginia. More than 100 of some 140 Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Gotham in the 1950s asked the same question and reached the same conclusion, pulling out their tax dollars and leading their well-paid workers into greener pastures in those pre–Rudolph Giuliani decades. They were among the million New Yorkers, many of them the elderly rich and the well-educated young, who fled Gotham in the 1970s and 1980s.

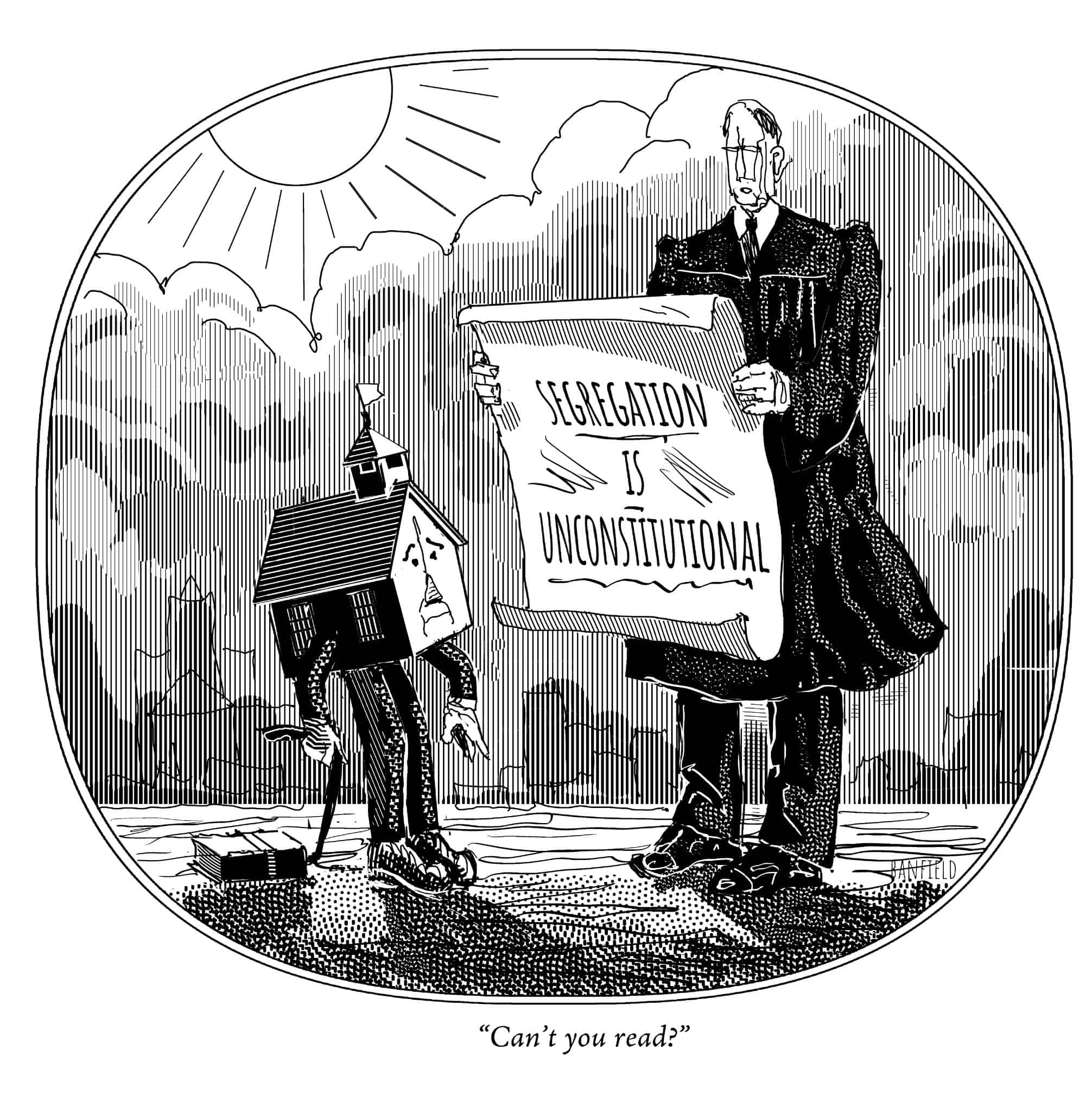

The squalor was only one problem. Another was crime. Of course, much of the disorder—the open dope-dealing, the public drinking, the streetwalkers serving every almost-unthinkable taste, the three-card-monte cardsharpers and their pickpocket confederates preying on the crowds they drew, the window-rattling boombox radios—was itself against the law. But these minor crimes deepened as a coastal shelf into burglary, car theft, armed robbery, assault, rape, and murder—one killing every four hours every day of the annus horribilis 1990.

Those New Yorkers who could afford it tried to insulate themselves with doormen and limo services, as in Tom Wolfe’s 1987 bestseller The Bonfire of the Vanities; those who couldn’t, like the protagonist of Saul Bellow’s 1970 Mr. Sammler’s Planet, envied the guarded doors, the trustworthy drivers, the hushed private clubs—islands of civility in a sea of chaos—as they held on to the strap of the lurching, graffiti-fouled bus, watching the pickpocket ply his craft, or walked down their own dark streets, adrenaline rushing at the sound of every footfall.

Just as the crack of a jungle twig cocks every ear, tenses every muscle, and sends birds screaming indignantly into the sky, apprehension was as characteristic a New York feeling as was ambition in those days. If we didn’t quite live in “continuall feare, and danger of violent death,” as in Thomas Hobbes’s state of nature, “where every man is Enemy to every man,” we were sufficiently on edge. And no wonder. One friend, robbed at gunpoint on Broadway of his wallet, which the thief searched for his address, was then marched to his apartment, forced to unlock it, and tied up, while the gunman coolly stuffed everything of value into my friend’s bedsheets and carted it off. For the sheer thrill, a gang of teen girls swarming up from Morningside Park stomped the girlfriend of a fellow graduate student unconscious and blood-drenched in front of the Columbia University president’s mansion one afternoon. A neighbor, pushed into his lobby as he unlocked his building’s unattended front door after a very long day’s work—the typical thief’s M.O. in that era—was not only robbed but also killed. Another friend, raped at knifepoint on a filthy hallway floor in a neighborhood where she had gone for a purpose she never mentioned, had her satisfied assailant ask her for another “date,” a proposal she declined. But in a way, on the street, in the subway, in the parks, we all felt continually violated and continually asked to go through it again. That people were leaving town all around us came as no surprise.

What to do? A Manhattan Institute seminar on Gotham school reform I attended in the late 1980s, as Koch’s 12-year mayoralty drew to a sadly sordid close, caught the temper of the times. Its chairmen were wily national teachers’ union chief Albert Shanker and New York Board of Education president Robert F. Wagner III, a long-valued friend. Maybe we could try X, a panelist suggested. No: union work rules forbade. How about Y? No: the state legislature . . . the budget. . . . And so on for two hours. The profoundly depressing expert consensus: the more you knew about New York, the more you knew that there was nothing nothing nothing we could do to fix a calamitous mess. After all, wasn’t this the “ungovernable city”? Continue reading →