Monticello Virtual Tour here

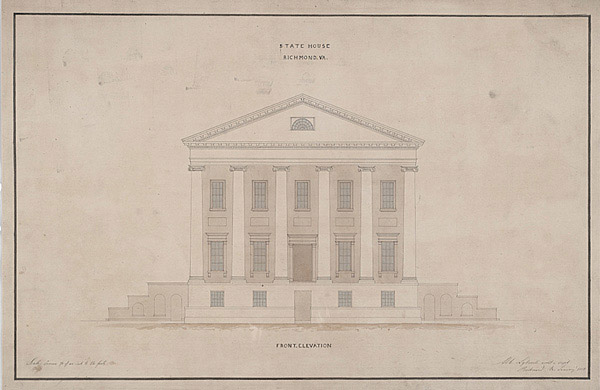

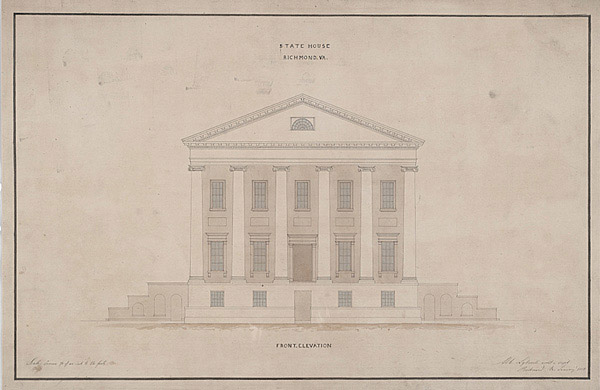

Jefferson was a passionate and highly informed amateur architect, who carefully studied the buildings of France, including the Roman Maison Carrée in Nîmes:

He used the Roman building as his model when he drew up his plans for the Virginia State Capitol, designed in 1786, while he was serving as U.S. minister to France.

It was completed in 1788, before he returned to America.

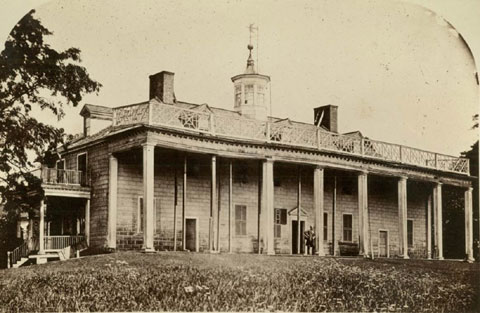

His first sketch of Monticello was much more Palladian than the version we have now.

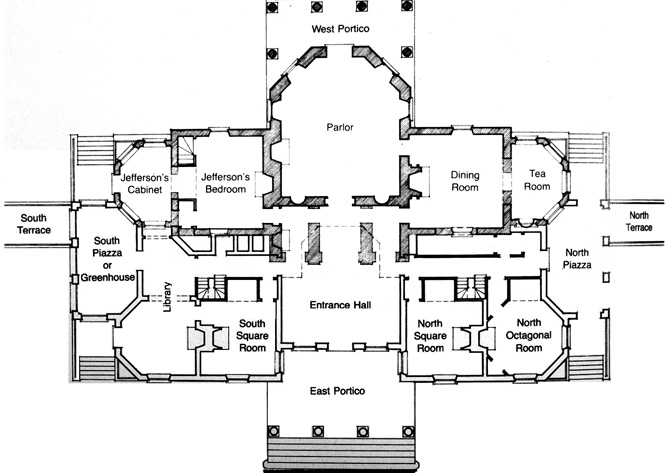

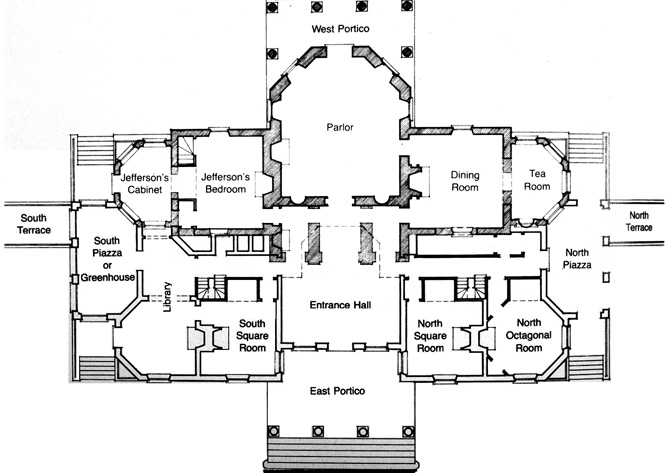

Here is a floor plan of the perfected version. If you click on each room, you will see a photograph of it, with some commentary on its furnishings, from the estimable Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Among the many brilliant technological innovations he employed in the house, here is the amazing clock he designed, with one face visible outside, on the facade, and the other inside, above the hall doorway. The technological marvel: the works must make each hour hand (there was no minute hand on the outer face) move in the opposite direction.

But when Jefferson’s fame drew swarms of uninvited visitors to Monticello, sometimes he would retreat to his remote and barely accessible lodge, Poplar Forest, a masterpiece in it own right, built from 1806 until his death 20 years later, near what’s now Lynchburg:

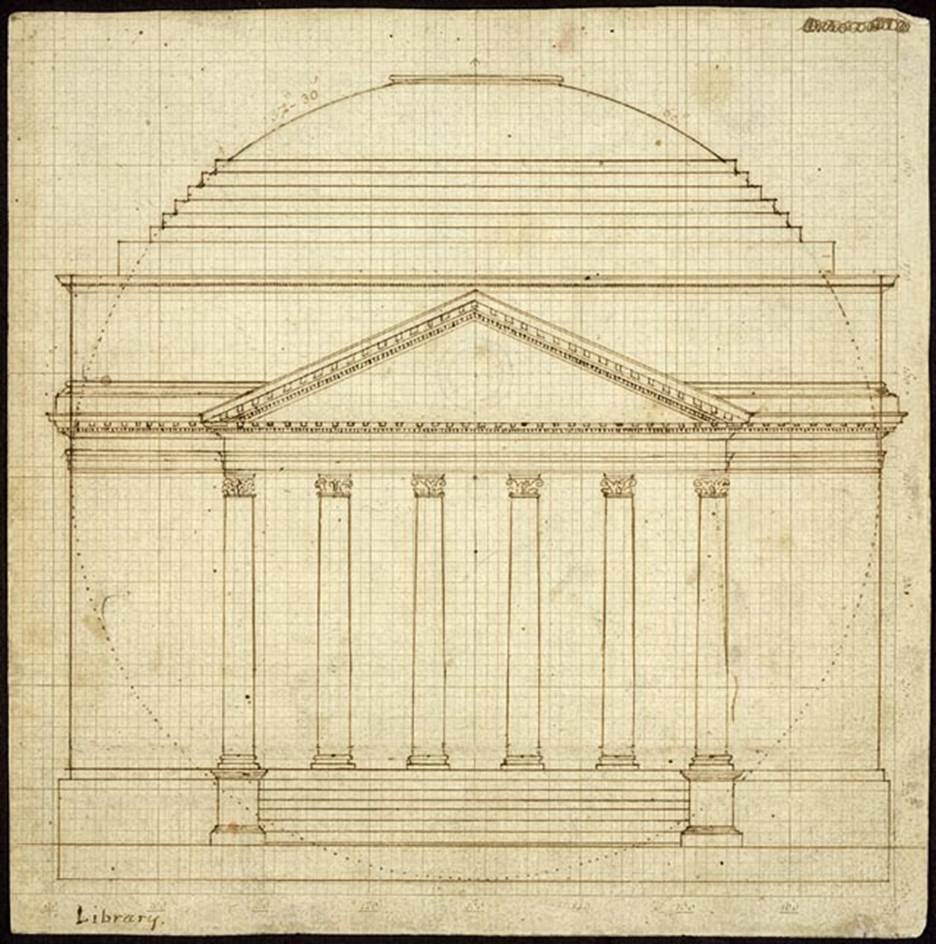

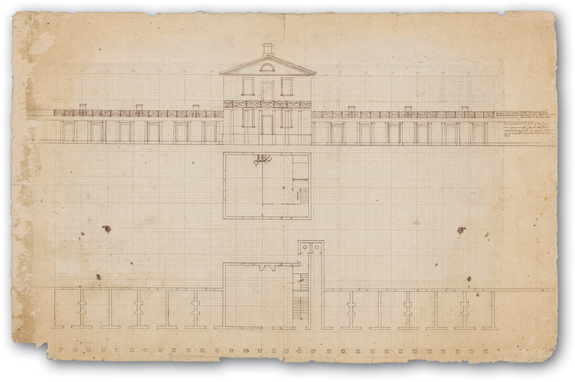

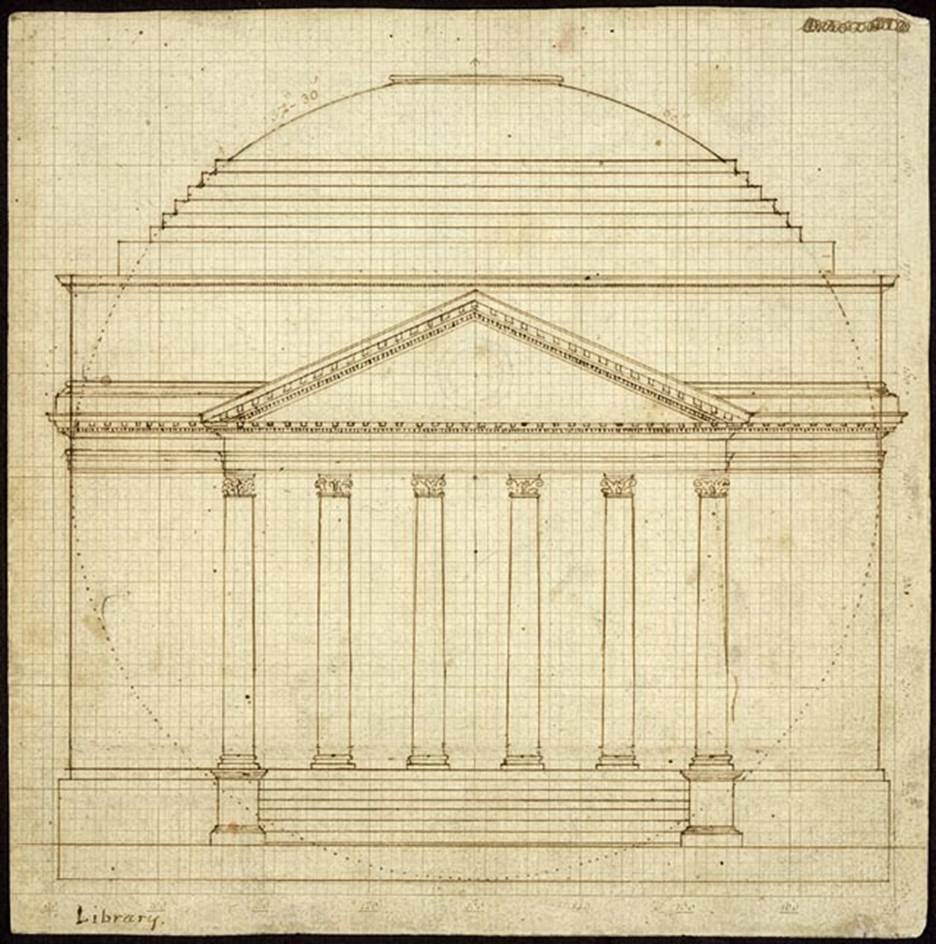

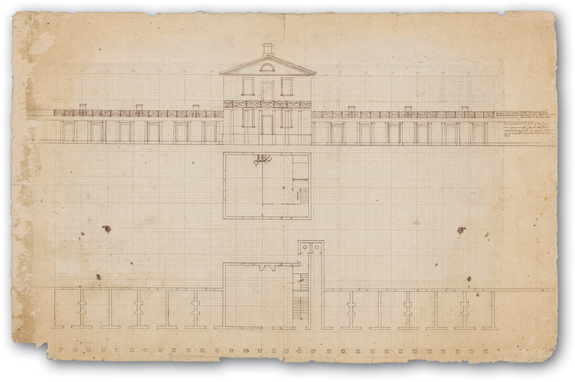

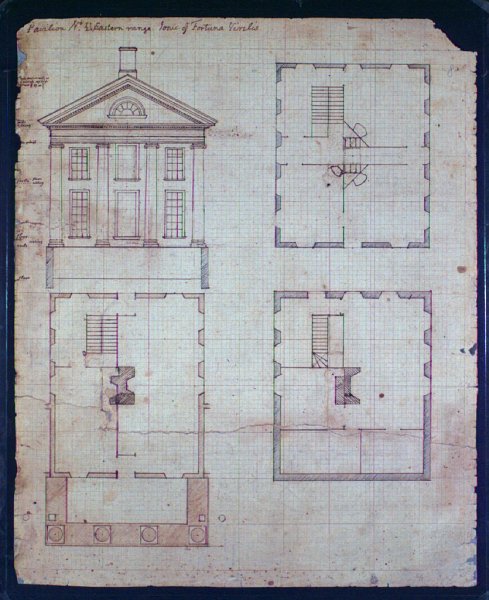

And of course he was the architect, in both the literal and figuarative sense, of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where he intended each pavillion of the campus to be a concrete example of a different style of classical architecture. These are his original 1814 drawings for some of the buildings.

The centerpiece of his plan was a remarkable classical library, the Rotunda.

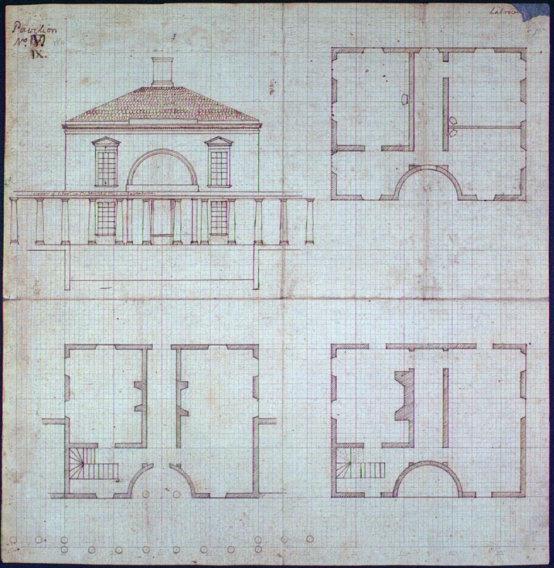

It was flanked by ten pavilions, and Pavilion IX is shown here to the left and Pavilion X to the right.

Designed for economy but envisioning expansion as needed, the plan called for the pavilions to be flanked by identical dormitories on each side, situated around three sides of a square and all connected by covered walkways. A chinoiserie railing recalls the treatment of the wings at Monticello. Each pavilion was to serve as a concrete illustration of an architectural style. (University of Virginia Library)

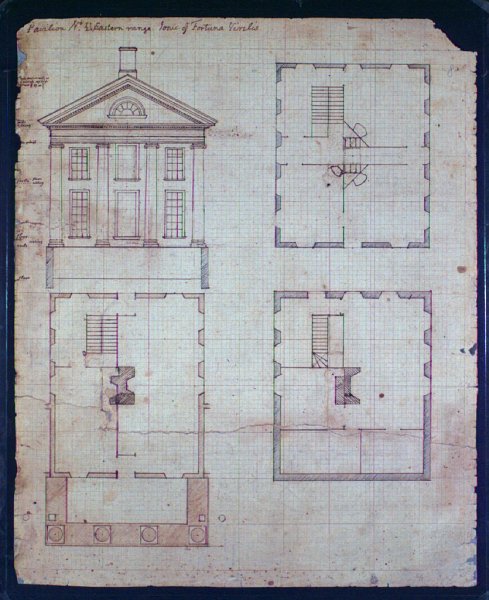

Pavilion II draws upon the Ionic order of the Roman Temple of Fortuna Virilis depicted in Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture.

Pavilion VI

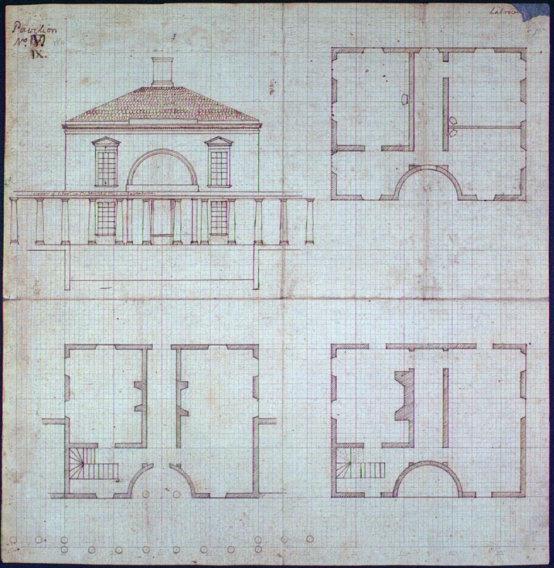

Pavilion VII combined suggestions from architect William Thornton with Jefferson’s own ideas for the first pavilion, basing its order on the Doric of Palladio. Its cornerstone was laid on October 6, 1817.

Pavilion IX

(University of Virginia Library)

Here is Kristie Heilenday’s rendering of the pavilions:

And here is an early view of The Lawn, as Jefferson called it: