How John Marshall Made the Supreme Court Supreme

Myron Magnet

Spring 2019

His brains and bonhomie forged a band of Federalist brethren.

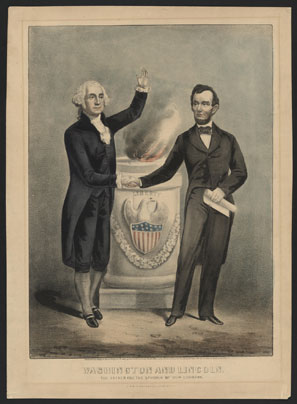

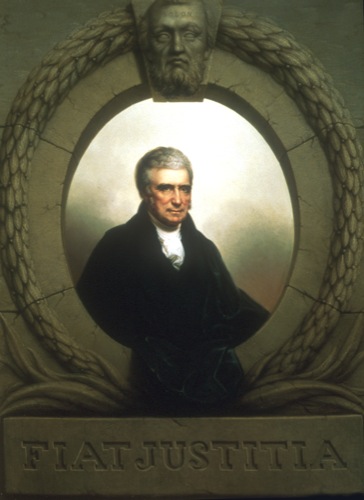

Most serious American readers know National Review columnist and National Humanities Medal laureate Richard Brookhiser as the author of a shelf of elegantly crafted biographies of our nation’s Founding Fathers, from George Washington and Alexander Hamilton up to our re-founder, Abraham Lincoln. Those crisp, pleasurable volumes rest on the assumption that these were very great men who created (or re-created) something rare in human history: a self-governing republic whose growing freedom and prosperity validated the vision they strove so hard and sacrificed so much to make real. It’s fitting that the most recent of Brookhiser’s exemplary works is John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court, for it was Marshall—a junior member of the Founding Fathers, so to speak—who made the Court a formidable bastion of the nation’s founding governmental principles, shielding them from attacks by demagogically inclined presidents from Jefferson to Jackson, until his death in 1835.

It takes all a biographer’s skills to write Marshall’s life, for he left no diaries and few letters or speeches. One must intuit the man’s character from bits and pieces of his own writings, his weighty but wooden biography of George Washington, his judicial opinions, and his contemporaries’ descriptions of him. From these gleanings, however, like Napoleon’s chef after the Battle of Marengo, Brookhiser concocts a rich and nourishing dish.

Born in backwoods Virginia in 1755, Marshall all his life kept a rural simplicity of manner and dress that once misled a Richmond citizen to think him a porter and ask him to carry a turkey home from the market, which the chief justice cheerfully did, refusing a tip for his efforts. Gregarious, athletic, and full of jokes, Marshall in his thirties was the life of the Quoits Club, a select Richmond group dedicated to weekly bibulous good fellowship and a horseshoe-like game played with metal rings, activities at which Marshall excelled. During one barroom game of inventing rhymes on assigned words, he drew “paradox” and, glancing at a knot of bourbon-drinking Kentuckians, promptly declaimed:

In the Blue Grass region,

A paradox was born.

The corn was full of kernels,

And the colonels full of corn.

“In his youth, he gamed, bet, and drank,” a temperate congressman grumbled; yet in old age, the legislator had to drive uphill in his gig, “while the old chief justice walks.”

Service in Washington’s army during the Revolution left Marshall with veneration for his commander in chief—“the greatest Man on earth,” he thought. Like most of his fellow officers, he came away from the war with the beliefs, born from the bone-chilling, stomach-gnawing privation of icy winter quarters, that became the core principles of Federalism once the Constitution was ratified—including by the Virginia ratifying convention, where Marshall played a key role. For its own preservation, the United States needed to be a real union, not a confederation of states, the Federalists held, with a central government powerful enough to fight a war and fund it, without inflicting superfluous suffering on its soldiers.

Continue reading