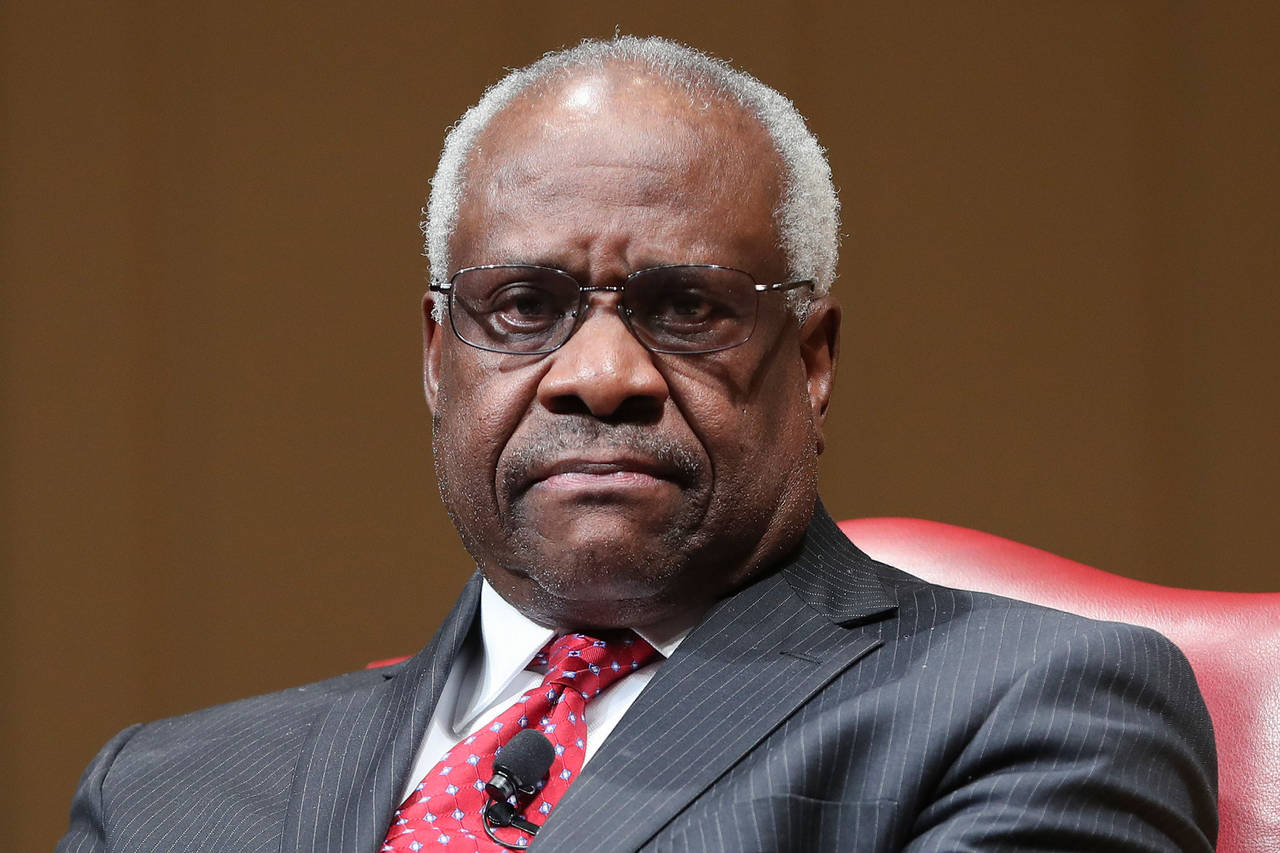

This month, Clarence Thomas, now the longest-serving Supreme Court justice, wrote a 5-4 opinion overturning a 40-year precedent on states’ individual sovereignty, and stood against all his colleagues except Ruth Bader Ginsburg in favor of armed services members suing the government for medical malpractice.

Thomas goes wherever the Constitution and the law as written lead, ideology be damned. And history will judge him a giant for it.

In Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt earlier this month, the Supreme Court ruled that a state cannot, without its own consent, be sued in another state’s courts, overruling the high court’s 1979 Nevada v. Hall decision. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the slim majority, stated that stare decisis, referring to the much-hyped practice of following well-grounded previous Supreme Court rulings, “does not compel continued adherence to this erroneous precedent.”

Liberal Justice Stephen Breyer wasted no time in his dissent, calling Thomas’s majority opinion “the absolute approach,” later asserting that “stare decisis requires us to follow Hall, not overrule it,.” Then the Clinton appointee slyly added: “See Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey” – Casey being the 1992 joint opinion of three Republican-appointed justices preserving the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion on demand, nullifying all 50 states’ various abortion laws.

The Constitution Trumps Flawed Precedent

“Overruling a case always requires ‘special justification,’” Breyer went on to write. “What could that justification be in this case? The majority does not find one.”

Clarence Thomas finds the Constitution of the United States to be “special justification” enough, and in this case he quotes Madison and Hamilton on how immunity from private lawsuits was integral to sovereignty. But Breyer was sending a not-too-subtle signal that Roewould soon be on the chopping block.

The Supreme Court also, on Monday, refused, 7-to-2, to hear Daniel v. United States, in which the husband of a Navy lieutenant sought to sue the federal government after his wife bled to death after giving birth at a naval hospital. In this case, Justice Ginsburg was with Thomas, who wrote an individual dissent calling, not for the first time, for the striking down of the 1950 Feres v. United States decision, which holds that military personnel injured due to a federal employee’s negligence can’t sue the government under the 1946 Federal Tort Claims Act.

Thomas pointed out in 2013, when the court refused another attempt to reconsider Feres, that the actual law only allows the government immunity when the injury is the result of “combatant activities of the military or naval forces, or the Coast Guard, during time of war.” Feres thus “has the unfortunate consequence of depriving servicemen of any remedy when they are injured by the negligence of the Government or its employees,” Thomas wrote.

A case like that makes you wonder if Thomas is the only current Supreme Court justice who reads the actual words of enacted statutes.

A Trail Future Justices Can Follow

Myron Magnet, editor-at-large of the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal and author of one of the most important books of the last 30 years, The Dream and the Nightmare: the Sixties’ Legacy to the Underclass, has devoted his newest work to the senior associate justice. In Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution, published this month, Magnet argues that “in the hundreds of opinions he has written in more than a quarter century on the court,” Thomas “has questioned the constitutional underpinnings of the new order and has tried to restore the limited, self-governing original one, as more legitimate, more just, and more free than the one that grew up in its stead.”

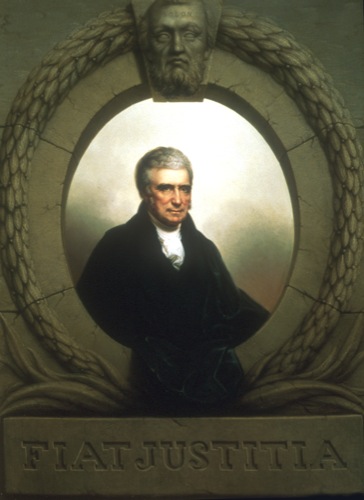

While Thomas’s legacy may not be fully evident today, Magnet believes “Like such other great dissenters as the first John Marshall Harlan or Antonin Scalia, he has blazed a trail to liberty that future justices can follow.”

Stare decisis “in modern times has been a handmaiden of judicial policy-making: judges tinker with the precedents until ‘they get what they want, and then they start yelling stare decisis, as though that is supposed to stop you,’ Thomas said in 2016 … An iron-bound allegiance to stare decisis, as the court has demonstrated more than once, can result in generations of error piled upon error,” Magnet warns.

“’I trust the Constitution itself. The written document is the ultimate stare decisis,’ Thomas argues. ‘Instead of saying stare decisis,’ he explained recently, ‘we should say quo warranto – by what authority?’”

A Supreme Court That Kept Blacks Unarmed

Magnet then plays tour guide to some of Thomas’s most insightful opinions, like 1995’s United States v Lopez, in which he used a congressional overreach of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause to point out that even supposedly legitimate uses of that provision might eventually “give Congress a ‘police power’ over all aspects of American life,” pointing out that “when asked [in oral argument] if there were any limits to the Commerce Clause, the Government was at a loss for words.”

According to Magnet, “Thomas’s magnum opus so far” is his concurrence in the 2010 McDonald v. Chicago decision, in which Chicago’s handguns-within-the-home prohibition was struck down. Thomas “utterly repudiates the Supreme Court’s most tragically wrong and history-changing decisions of them all, the Slaughter-House Cases and United States v. Cruikshank, the two cases … that strangled Reconstruction in its cradle and licensed the generations-long grip of Jim Crow on black Southerners.”

White Southerners in the aftermath of the Civil War did not want freed blacks able to arm themselves, so only five years after the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification the new amendment was falsely interpreted by the Supreme Court as not applying the Bill of Rights – including Second Amendment gun rights – to the states.

“Cruikshank’s holding that blacks could look only to state governments for protection of their right to keep and bear arms enabled private forces, often with the assistance of local governments, to subjugate the newly freed slaves and their descendants through a wave of private violence designed to drive blacks from the voting booth and force them into peonage, an effective return to slavery,” Justice Thomas wrote. “Without federal enforcement of the inalienable right to keep and bear arms, these militias and mobs were tragically successful in waging a campaign of terror against the very people the Fourteenth Amendment had just made citizens.”

The Second Amendment suppressed for white supremacist purposes. Imagine.

The “substantive due process” doctrine used by the others in the McDonald majority, as venerable and oft-used over many years as it may be, repeatedly “applies rights against the States that are not mentioned in the Constitution at all, even without seriously arguing that the Clause was originally understood to protect such rights,” Thomas noted, citing Roe and 1905’s Lochner v. New York, a discredited ruling that held that laws limiting working hours violated the due process clause.

Thomas called the doctrine “a legal fiction” that “fails to account for both the text of the Fourteenth Amendment and the history that led to its adoption, filling that gap with a jurisprudence devoid of a guiding principle. I believe the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment offers a superior alternative, and that a return to that meaning would allow this Court to enforce the rights the Fourteenth Amendment is designed to protect with greater clarity and predictability than the substantive due process framework has so far managed.”

Thomas reminded his colleagues: “stare decisis is only an ‘adjunct’ of our duty as judges to decide by our best lights what the Constitution means.”

Experts Vs. The People Themselves

Clarence Thomas’s life experience was a near-perfect prelude to his becoming champion of the true, plain meaning of the Constitution. Growing up in poverty in segregated Savannah, Georgia, raised by a grandfather whose love for him manifested itself in harshly demanding responsibility of him, with no excuses allowed; “flirting with and rejecting black radicalism at college,” as Magnet notes, “and running one of the myriad administrative agencies that the Great Society had piled onto the New Deal’s batch – an agency that supposedly advanced equality – he doubted that unelected experts and justices really did understand the moral arc of the universe better than the people themselves. He had seen how the rules and rulings they issued too often made lives worse, not better.”

Justice Breyer apparently has the company of pro-life lawmakers in Alabama, Louisiana, Missouri and other states in believing stare decisis will not protect Roe v. Wade from the current composition of the court on which he sits. If they’re right, it won’t be “the absolute approach” that wins. It will be the unaccountable “permanent constitutional convention, continually making and remaking the law,” as Magnet calls it, that at long last loses.