Myron Magnet

Liberty or Equality?

The Founding Fathers knew that you can’t have both.

Spring 2014

With the fulminating on the left about inequality—“Fighting inequality is the mission of our times,” as New York’s new mayor, Bill de Blasio, summed up the theme of his postelection powwow with President Barack Obama—it’s worth pausing to admire anew the very different, and very realistic, modesty underlying Thomas Jefferson’s deathless declaration that all men are created equal. We are equal, he went on to explain, in having the same God-given rights that no one can legitimately take away from us. But Jefferson well knew that one of those rights—to pursue our own happiness in our own way—would yield wildly different outcomes for individuals. Even this most radical of the Founding Fathers knew that the equality of rights on which American independence rests would necessarily lead to inequality of condition. Indeed, he believed that something like an aristocracy would arise—springing from talent and virtue, he ardently hoped, not from inherited wealth or status.

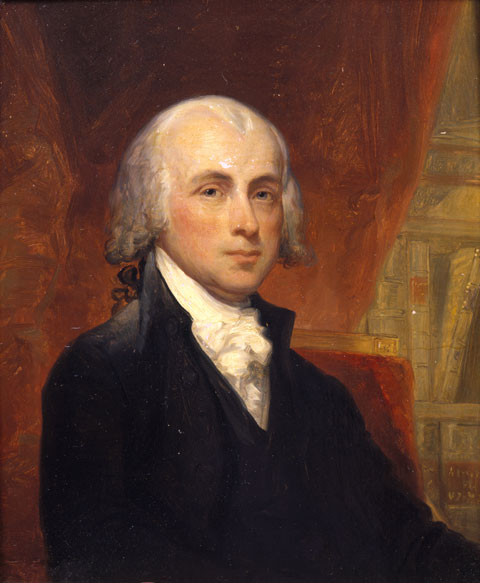

In the greatest of the Federalist Papers, Number 10, James Madison explicitly pointed out the connection between liberty and inequality, and he explained why you can’t have the first without the second. Men formed governments, Madison believed (as did all the Founding Fathers), to safeguard rights that come from nature, not from government—rights to life, to liberty, and to the acquisition and ownership of property. Before we joined forces in society and chose an official cloaked with the authority to wield our collective power to restrain or punish violators of our natural rights, those rights were at constant risk of being trampled by someone stronger than we. Over time, though, those officials’ successors grew autocratic, and their governments overturned the very rights they were supposed to protect, creating a world as arbitrary as the inequality of the state of nature, in which the strongest took whatever he wanted, until someone still stronger came along.

In response, Americans—understanding that “kings are the servants, not the proprietors of the people,” as Jefferson snarled—fired their king and created a democratic republic. Under its safeguard of our equal right to liberty, each of us, Madison saw, will employ his different talents, drive, and energy, to follow his own individual dream of happiness, with a wide variety of successes and failures. Most notably, Federalist 10 pointed out, “From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results.” That inequality would be a sign of the new nation’s success, not failure. It would mean that people were really free.

The democratic republic that the American Revolution brought into being, however, contained the seeds of a new threat to natural rights, Madison fretted. Yes, the new nation will operate by majority rule, but even democratic majorities can’t legitimately overturn the fundamental rights that it is government’s purpose to safeguard, no matter how overwhelming the vote. To do so would be just as grievous a tyranny as the despotism of any sultan in his divan. It would be, in Madison’s famous phrase, a “tyranny of the majority.” As Continental Congressman Richard Henry Lee put it, an “elective despotism” is no less a despotism, for all its democratic trappings.

How would such a tyranny occur? Almost certainly, Madison thought, it would center on “the apportionment of taxes.” Levying taxes “is an act which seems to require the most exact impartiality, yet there is perhaps no legislative act in which greater opportunity and temptation are given to a predominant party, to trample on the rules of justice. Every shilling with which they overburden the inferior number is a shilling saved to their own pockets.” How easy for the unpropertied many to expropriate the wealth of the propertied few by slow erosion, decreeing that they should pay more than a proportionate share of the public expenses. How seductive for the multitudinous farmers to levy taxes on the much smaller number of merchants or bankers or manufacturers, while exempting themselves. How tempting for the majority who have debts to transfer money secretly and silently away from the minority who are their creditors by debasing the currency, so that the real value of what they owe steadily shrinks, as Madison well remembered from the ruinous inflation of the Revolutionary War years. And a year before the Constitutional Convention, Madison recalled, the debt-swamped farmers of western Massachusetts had cooked up, in Shays’s Rebellion, still more “wicked and improper” schemes for expropriating the property of others: trying to close the courts at gunpoint to prevent foreclosures on their defaulted mortgages and even demanding the equal division of property.

So as chief architect of the Constitution, designed to give the federal government sufficient power to protect citizens’ basic rights—above all, the power to tax, whose lack under the Articles of Confederation had made the Revolutionary War longer and grimmer than it would have been if Congress had had sufficient means to buy arms and pay soldiers—Madison proceeded with his heart in his mouth, fearful that such augmented power made a tyranny of the majority all the more possible. His main challenge at the Convention, as he saw it, was to guard against precisely that outcome. So while four of the 18 specific powers that Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress concern the levying of taxes and the borrowing and coining of money to “provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States”—taxes that “shall be uniform throughout the United States”—eight of the rest deal with spending only for military and naval purposes, while the “general welfare” powers extend only to building post offices and post roads; establishing federal courts; protecting intellectual property by copyrights and patents; and regulating bankruptcies, naturalization, and interstate and foreign commerce. Not content merely to limit and define explicitly the federal government’s power, Madison made sure that the Constitution divided it up among several branches, limiting the power that any single individual or official body could wield and putting each jealously on guard against any other’s attempt to seize a disproportionate share. Moreover, all these officials (except the judges) were elected representatives of the people: they were the agents through whom Americans, who had no rulers, governed themselves.

But why was the liberty that Madison so mightily struggled to protect so precious? Americans knew how grievous its opposite was, both from the enslaved blacks they saw all around them as well as from their knowledge that their own forebears had fled British persecution of non-Anglican Protestants or European persecution of all Protestants, denied even freedom to express their own beliefs. They knew what man could inflict on man. But of all the Founders, Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton gave the most positive, eloquent, and inspiring answer to that question—though, in fact, he thought that he was answering a question about economics. Illegitimate, orphaned, and poor, Hamilton dreamed big dreams as a teenage clerk, sitting on his countinghouse stool on a small West Indian island whose only business was sugar and slaves. Ambition burned within him, along with a keen but unformed sense of his own talent. He knew he could be something other than he was. But what or how, he didn’t foresee. Maybe a war would come, he daydreamed, and give him his chance.

It did come. By then, through some fairy-tale-like strokes of good fortune, he found himself in New York, studying at King’s College (later Columbia). With eighteenth-century student activism, he dropped out of school, joined the army, rose—by dint of the talent he knew he had—to be General Washington’s right-hand man and then, with national independence won and Washington elected president, his Treasury secretary.

If the liberty that America had secured through the war was going to be about pursuing your own happiness in your own way, then Hamilton aimed to create an economy that would give his fellow citizens the fullest opportunity to do so, through a limitless variety of career possibilities. America shouldn’t just be an agricultural country, he knew. It should teem with industry, trade, finance, everything imaginable. And opportunity would breed opportunity, as human ingenuity and curiosity—the most valuable natural resources of all—came up with new inventions, new discoveries, new ways of doing things, new ways of using already-existing things. “The bowels as well as the surface of the earth,” Hamilton wrote, will be “ransacked for articles which were before neglected. Animals, Plants, and Minerals acquire an utility and value, which were before unexplored.” The wealth of the nation and of individuals will mushroom, he saw, and America’s opportunity economy would be a mighty engine of upward mobility. To this end, he established a financial system that made credit for setting up new enterprises plentiful, and, when he came to establish the new U.S. mint, he made sure that it would strike coins of very small denomination, to ensure that even the humblest could rise through the enrichment machine he had set in motion.

But the opportunity Hamilton had in mind wasn’t just the chance to get rich. Musing on his clerk’s stool in Saint Croix, he had feared that the fire burning within him would just gutter out if he found no outlet for his genius. The best minds, he concluded from his own experience, “labour without effect, if confined to uncongenial pursuits.” In a free, opportunity society, by contrast, “each individual can find his proper element, and can call into activity the whole vigour of his nature.” The purpose of such a society is moral as well as practical. “To cherish and stimulate the activity of the human mind, by multiplying the object of enterprise,” is a kind of soulcraft. Much of what we can make of our single life—or even imagine making of it—depends on the kind of society around us. The liberty and opportunity that the United States would afford, Hamilton believed with all his fiery intensity, would allow individuals to realize every God-given potential and to become all that they had it within themselves to be. It’s hard to imagine a higher aspiration for your fellow man than that.

When we see the same faults followed by the same misfortunes,” Madison wrote, “we may reasonably think that if we could have known the first we might have avoided the others.” So, against the liberty and opportunity central to the Founding American vision, which produced two centuries of freedom and prosperity unmatched in history, what have the dreams of equality yielded? At the outermost extreme, the French upheaval for égalité in 1789 and the Russian drive toward a classless society in 1917 drenched every inch of their respective countries in blood and immeasurably decreased the stock of human happiness and freedom for years to come. To be sure, even a Bill de Blasio cherishes no such radical fantasies, and if Barack Obama ever flirts with them, he keeps it to himself.

But there is an American version of that impulse that dates back at least to Shays’s Rebellion, with its dream of an equal division of property. In the twentieth century, it most dramatically reshaped the nation whenever a “progressive” president like Obama joined forces with a “progressive” New York mayor like de Blasio to redistribute wealth through unequal taxation—in a way that Madison would have seen as a betrayal of his most fundamental beliefs, sure to end badly. It began in the Great Depression, which convinced Franklin Roosevelt and Fiorello La Guardia that individuals were too puny, powerless, and insignificant to shape their fates in a world seemingly governed by vast, impersonal forces that only a vast and mighty government could match. Indeed, because FDR thought that the Depression was a crisis of overproduction, he also concluded that the Hamiltonian vision of invention, discovery, and creation had grown obsolete. The age of production was over, and the age of redistribution had begun, with government the only fair and wise arbiter of who should get what.

Roosevelt, while still New York’s governor, had already begun to provide cash welfare to the indigent in 1931, and when he introduced the program nationally as president, La Guardia upped the ante, quadrupling the federal dole in New York City with state and city funding, though FDR soon ended the means-tested national program as demeaning to recipients and replaced it with relief tied to work. By the Depression’s end, La Guardia had built the nation’s first archipelago of subsidized housing projects—nine in all—along with publicly funded hospitals, and he spent taxpayer dollars to take over and subsidize the city’s subway and bus lines and to establish a municipal health-insurance system. So for some, housing, health, and transportation were now the government’s responsibility, paid for by others. With the Depression over, a 1943 race riot convinced the mayor that taxpayer dollars still needed to flow into the welfare system, in ever-increasing amounts, to create racial justice.

Karl Marx was partly right in saying that, when history repeats itself, it happens the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. For the next collaboration of a “progressive” president and New York mayor to reduce inequality—that of Lyndon Johnson and John Lindsay—certainly began as farce but ended in a tragedy that continues to unfold to this day. Picking up the New Dealers’ torch, Lindsay fell over himself with eagerness to make New York a demonstration project for Johnson’s War on Poverty—a grotesque failure that, on its 50th anniversary this year, mainstream reporters too young and uninformed to know better have striven to repaint as a success.

Johnson’s originally Hamiltonian impulse “to give our fellow citizens a fair chance to develop their own capacities” took as its operating model a cockeyed, far-left New York City community-organizing program, the chief self-development activity of which was to protest noisily against “the System”—Hamilton’s American capitalism, that is to say—which the community organizers deemed too racist and inequitable ever to provide opportunity. Lindsay himself, as cockeyed as the community organizers, decided that he could make impoverished black New Yorkers into middle-class citizens by building them public housing projects in middle-class neighborhoods, giving them middle-class-style control of their public schools, and generating middle-class incomes through a greatly expanded and enriched Depression-era cash welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children—administered with such lax oversight that the city’s welfare commissioner earned the nickname “Come-and-Get-It Ginsberg.” Despite War on Poverty funding, these projects required Lindsay’s imposition of a city income tax in 1966, in addition to the state and federal taxes that New Yorkers already paid.

Though the 1913 ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment—levying the first permanent income tax, with unequal, graduated rates—cracked open the door to Madison’s dreaded tyranny of the majority, it was only in the Depression that radical income redistribution became national policy. It stayed so for half a century, until the Reagan administration gradually lowered income-tax rates and made them less unequal. But thereafter, radical redistribution resumed, so that by 2010, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the top-earning 40 percent of households paid 106.2 percent of U.S. income taxes, while the bottom 40 percent, because of refundable tax credits such as the earned income-tax credit and the child tax credit, paid minus 9.1 percent. That bottom 40 percent received an average $18,950 in transfer payments—including not just the refundable tax credits but also such means-tested benefits as food stamps and Medicaid, as well as payments from Medicare and Social Security, programs to which they indeed contributed; but Social Security is nevertheless an income-transfer scheme, in that low-income recipients get paid back at higher rates than better-off recipients. As for the nonworking poor on welfare, a New York family of four living in subsidized housing, with food stamps, Medicaid, and other means-tested benefits, receives the equivalent of $40,000 a year—more than double what a 40-hour-a-week minimum-wage job pays in the city, though not counted in the government’s official income statistics.

The fact that the Internal Revenue Service that collects all this money for the government to redistribute does so without observing “the most exact impartiality” that Madison urged but rather engages in schemes “to trample on the rules of justice”—as Kimberley Strassel’s exemplary Wall Street Journal reporting on the agency’s suppression of Tea Party groups has shown—would be one more proof to Madison that “[i]n framing a government of men over men the great difficulty is this: You must first enable the government to control the governed, and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.”

Now that President Obama has turned into a Brobdingnagian government power grab the governmental takeover of health care that began modestly with Mayor La Guardia and that ballooned with the War on Poverty’s creation of Medicaid and Medicare, America will more resemble the fiscally unsustainable European welfare states than the U.S. under the Madisonian Constitution. As government spending rises—in part because the president “has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance,” as Jefferson complained in the Declaration of Independence—less of the private capital and ready credit that Hamilton foresaw as an engine of opportunity for ordinary citizens to build businesses and create upward mobility for themselves and their employees remains available. Moreover, the array of new taxes concealed within the so-called Affordable Care Act, as well as its income-redistribution subsidies, will further clog the gears of the opportunity machine. In California’s Monterey County, for instance, a 54-year-old part-time worker making $18,000 annually will pay $1 a month for the same mid-range policy that will cost a 54-year-old with a $60,000 annual salary $848 a month—almost 18 percent of his pretax income, with almost triple the maximum yearly out-of-pocket co-pays, according to a California Health Benefit Exchange website. He’d pay $1,412 a month if he should have the bad judgment to marry the $18,000-a-year part-timer (though the Kaiser Family Foundation gives slightly lower estimates). Thanks to sluggish economic and stagnant employment growth, for the younger generation of Americans, it’s already no longer true that “each individual can find his proper element, and can call into activity the whole vigour of his nature.” The liberty to be whatever your talents might allow you to become has shriveled and could continue to shrivel toward a European dearth of opportunity.

The liberty to choose something as important as your own health care has also shrunk, unless you’re very rich, so inequality has also widened. One can’t help hear the echo of Richard Henry Lee’s phrase, an “elective despotism,” when recalling that Congress—which passed the Affordable Care Act by the slimmest of majorities, without bothering to read it—set up an appointive board, largely unanswerable to the people’s elected representatives, to make Obamacare’s most important decisions, greatly expanding the undemocratic administrative apparatus that increasingly governs the country by edict; or when one recalls that President Obama unconstitutionally changed the law, also by edict, with a casual stroke of that pen, imposing by diktat what the legislature won’t legislate. Nothing Madisonian there.

George Washington and many of his fellow Founders believed that a special kind of culture, one that nurtures self-reliance and a love of liberty, was essential to keeping alive the free Constitution over whose creation he had presided. Just as that spirit has guttered out in welfare-state Britain, once home to the “free-born Englishman,” it can dim here, too. Blather from government officials about the unjust inequality of American society—on top of a generation’s worth of hot air from the universities, the mainstream media, and the multibillion-dollar antibusiness entertainment industry about how Hamiltonian, Madisonian America oppresses a wide range of aggrieved victims, while poisoning the air, the water, and the very earth itself (though, of course, human ingenuity can solve every problem human ingenuity creates)—all this inexorably erodes the spirit of self-reliance, enterprise, and opportunity that animated the Founders, in their justified faith that they were creating a unique innovation in government that would immeasurably advance the happiness of mankind.

It is possible to demoralize an entire people and stifle their faith in the future and in themselves. The welfare underclass, filled with aggrieved resentment and void of hope, is the most extreme case in point. Their demoralization is pure gold to the ever-aggrandizing government, though—since here is the ultimate victim class that justifies the whole scheme of redistribution under the control of wise and mighty “rulers,” as Jefferson would have called them. Nevertheless, despite their material comfort—which includes the latest sneakers, flat-screen TVs, angry rap downloads, junk food galore, and bigger apartments than many middle-class Europeans can afford—the spiritual poverty that besets many of the underclass, the tawdry content of their character, is chilling, and ought to give pause to any supporter of the huge, redistributionist welfare-state project. Because man makes the meaning of his life himself, through work, through family, through community, it is not easy for a person kept by government, from womb to tomb, like a gerbil in a cage, to retain a sense of dignity and purpose. Is this really what we want for him? Nor is it easy for someone branded his victimizer, and taxed unequally to support him and the army of bureaucrats who live by claiming to make sure he gets his due, to retain with confidence his own sense of dignity and purpose.

Hamilton and Madison had a much larger and nobler sense of human possibility.

Myron Magnet, City Journal’s editor-at-large and its editor from 1994 through 2006, is a recipient of the National Humanities Medal. His latest book is The Founders at Home.