Clarence Thomas, the Repairer of Our Constitution

SEPTEMBER 10, 2019|

Justice Clarence Thomas, Myron Magnet

Clarence Thomas, the Repairer of Our Constitution

by RALPH ROSSUM|

During the 28 years that Clarence Thomas has served as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, he has written approximately 560 majority, concurring, and dissenting opinions. Myron Magnet has undertaken an insightful analysis of Thomas’s major opinions and his many speeches and addresses. The historian and editor-at-large of City Journal convincingly demonstrates that in those opinions and speeches, Thomas has articulated a clear and consistent jurisprudence of constitutional restoration that seeks to retrieve the original meaning of the Constitution—what the author calls “the lost Constitution.”

Pursuing an originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, Thomas has been unswayed by the claims of precedent—by the gradual build-up of interpretations that, over time, can obscure the original meaning of the constitutional provision in question and encourage activist justices to reach results-oriented and consequentialist decisions. As with too many layers of paint on a delicately carved piece of furniture, precedent based on precedent—focusing on what the Court has, in past cases, said the Constitution means as opposed to focusing on what the 1787 document actually means—hides the constitutional nuance and detail that Thomas would restore.

He is unquestionably the justice who is most willing to reject this build-up, this excrescence, and to call on his colleagues to join him in scraping away past precedent and getting back to bare wood: to what the Constitution originally meant. Just how willing Thomas is to toss precedent aside is apparent in Eastern Enterprises v. Apfel (1998), in which he indicated that the 200-year-old precedent of Calder v. Bull (1798) incorrectly interpreted the ex post facto clauses of Article I, Sections 9 and 10 to apply only to criminal matters and not civil matters.

His Grandfather’s Son

Magnet describes himself as “not a constitutional law professor but a writer.” And a fine writer he is! Moreover, his knowledge of the political thought of the Founding generation and his clear grasp of case law rival that of the best constitutional law professors. He has written “a life-and-works book in which life and works mutually illuminate each other to a greater than usual degree.” Thus he offers a thorough biographical sketch of his subject, one that concisely summarizes Thomas’s 2007 memoir, My Grandfather’s Son.

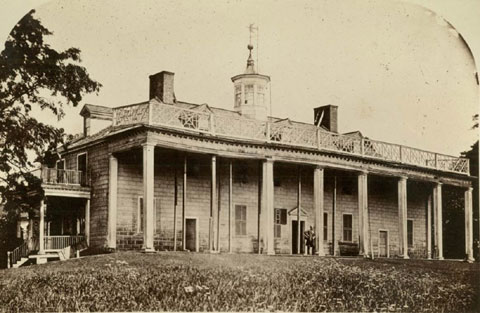

The biographical chapter will prompt many to want to read the memoir in its entirety (or listen to the audio book that Thomas himself narrates). In it Magnet brings out how the justice’s hardscrabble early life in Pinpoint, Georgia; his upbringing by his stern but loving grandfather in segregated Savannah, Georgia; his seminary, Holy Cross, and Yale Law experiences; his public service in the Missouri Attorney General’s office and federal agencies (the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission); and, his bruising Senate confirmation, all contributed to his views once on the Court, on such matters as equality and race, affirmative action, property rights, the right to keep and bear arms, and freedom of speech and the press.

The book then turns to how the Constitution came to be “lost.” Magnet calls this chapter “Who Killed the Constitution?” but here he overstates the matter. For he will later describe the Constitution as not dead but “vandali[zed],” and he has no doubt that “it is vandalism” that Thomas and other originalist justices following his lead can repair.

For Magnet, the original Constitution established a “small government of limited and enumerated powers” that has been lost to us for “nearly a century” because of 1) the post-Civil War Supreme Court’s “subversion” of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, 2) the late-New Deal Supreme Court’s Commerce Clause jurisprudence and its acceptance of the administrative state with independent agencies “acting as a fourth branch of government,” and 3) the Warren Court’s embrace of the doctrine of the “living constitution,” making it, in effect, “a permanent constitutional convention, continually making and remaking the law, to adapt, in a kind of Darwinian evolution to changing circumstances.”

Originalism in Action

Next comes “Originalism in Action,” and with that, we enter the “works” part of the “life-and-works” structure of Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution. Here we read of Thomas’ major opinions (mostly concurrences and dissents) and get an idea of what he has done to save what was lost and repair what has been vandalized. With admirable concision and clarity, this 47-page chapter keeps the justice’s arguments front and center.

Magnet addresses, at considerable length, Thomas’ attempt to overturn the post-Civil War Court’s evisceration of the Privileges or Immunities Clause in the 1873 Slaughter-House Cases. In McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), a five-member majority incorporated the Second Amendment, which secures an individual right to keep and bear arms, to apply to the states.

In a rather mechanistic application of substantive due process, Justice Samuel Alito held for four justices that the right to keep and bear arms was a liberty interest protected from state interference by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thomas supplied the fifth vote, but as a son of the segregated American South, he relied instead on the Privileges or Immunities Clause, arguing that the right to keep and bear arms secured by the Second Amendment was a privilege and immunity of citizens of the United States that no state can abridge.

The majority in Slaughter-House had argued to the contrary; it claimed that the “Privileges or Immunities of citizens of the United States” were few in number and limited to such matters as free access to the nation’s seaports, protection on the high seas, and use of the navigable waters of the United States. Most assuredly, they did not include those rights spelled out in the Bill of Rights.

Slaughter-House led inexorably to United States v. Cruikshank (1876), in which the Court failed to vindicate the rights of the freedmen of the state of Louisiana.

On Easter Sunday 1873, approximately 150 black Republicans were killed in Colfax, Louisiana, for exercising their First Amendment right “peaceably to assemble” in what Eric Foner has called “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction Era.” When the state failed to prosecute the perpetrators, federal authorities indicted their leaders for violating the 1870 Enforcement Act making it a crime for individuals to interfere with U.S. citizens exercising their privileges and immunities under the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Cruikshank, however, a unanimous Court, relying on Slaughter-House, denied that First Amendment rights were privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States and concluded that the Enforcement Act could not be used to prosecute those responsible for what came to be known as the Colfax Massacre. If First Amendment rights were not privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, neither was the right to keep and bear arms secured by the Second Amendment. Without federal enforcement of the freedmen’s right to keep and bear arms, Thomas observed, the Ku Klux Klan was able to “subjugate these newly freed slaves and their descendants through a wave of private violence designed to drive blacks from the voting booth and force them into peonage, an effective return to slavery.”

For Justice Thomas, Cruikshank was “not a precedent entitled to any respect,” and neither was Slaughter-House.

Magnet calls Thomas’s concurrence in McDonald his “magnum opus to date,” a “textbook demonstration of his method of judging. Here, with characteristic skepticism toward stare decisis, he utterly repudiates the Supreme Court’s most tragically wrong and history-changing decisions of all that strangled Reconstruction in its cradle and licensed the generations-long grip of Jim Crow on black Southerners.”

It should be noted that McDonald was Thomas’s first opportunity after his elevation to the Supreme Court to vote on the incorporation of a Bill of Rights provision to apply to the states. He had a second occasion earlier this year, when he voted in Timbs v. Indiana to incorporate the excessive fines provision of the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment to apply to the states. Even though the issue had nothing to do with race or the right to keep and bear arms, Thomas again wrote separately to indicate that the provision should be incorporated not because of substantive due process but because the protection against excessive fines is a privilege and immunity of citizens of the United States. (The case goes unmentioned by Magnet because his book was already in production when it was decided.)

Magnet also takes up how Thomas has gone to work repairing the constitutional vandalism inflicted, this time, by the late-New Deal Supreme Court in its Commerce Clause jurisprudence. Thomas, he argues, has consistently sought to overturn the Court’s longstanding “substantial effect on commerce” test, for two reasons.

First, as Thomas declared in his concurring opinion in United States v. Lopez (1995), the test renders “wholly superfluous” many of “Congress’ other enumerated powers under Article I, Section 8.” As he pointed out, the powers to tax and borrow, coin money, establish post offices and post roads, grant copyrights and patents, enact bankruptcy laws, declare war, and raise and support an army and navy—all have a substantial effect on commerce and are therefore rendered superfluous. In his mind, any interpretation of the Commerce Clause that does so “cannot be correct.”

Second, Thomas argues that the “substantial effects” test strikes a serious blow at federalism by giving Congress a police power over all aspects of American life. Since it effectively converts the federal government from one of delegated powers to one of reserved powers, it makes the rise of the administrative state even more pernicious and threatening to liberty. Congress delegates to independent agencies the power to enact, enforce, and adjudicate rules (itself a major violation of the Constitution’s separation of powers) on matters only reachable by the federal government because of the “substantial effects” test.

Thomas has sought to overturn Court precedents that require courts to defer to an executive branch agency’s reasonable interpretation of ambiguous language in a statute it is charged with executing, and even to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of ambiguous regulations that it has itself promulgated.

Magnet carefully takes the reader through Thomas’s concurring opinions in two relevant cases from 2015: Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Association and Michigan v. EPA. He quotes from Thomas in Michigan: Deference forces judges “to abandon what they believe is the ‘best reading of an ambiguous statute’ in favor of an agency’s construction. It thus wrests from Courts the ultimate interpretive authority to ‘say what the law is.’”

Roberts Challenges His Colleagues

Finally, Magnet takes up what Thomas has done to challenge the doctrine of the living Constitution. Examples abound. One is Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s contention in Grutter v. Bolinger (2003) that diversity is a compelling state interest for the University of Michigan Law School to accept students on the basis of race—but that, 25 years hence, it will not be. Thomas dissented, declaring that “the Law School’s current use of race violates the Equal Protection Clause” and insisting “that the Constitution means the same thing as it will in 300 months.”

Then there was Justice John Paul Stevens’ opinion in Kelo v. New London (2005), which had the effect of reading “public use” out of the Takings Clause, prompting Thomas to declare: “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not. I do not believe that this Court can eliminate liberties expressly enumerated in the Constitution.”

Still another example is Chief Justice John Roberts’ claim in Carpenter v. United States (2018) that the Court-invented notion (from a concurring opinion by Justice Harlan in the 1968 case of Katz v. United States) of a “reasonable expectation of privacy” required the FBI to obtain a search warrant before it obtained cell-tower location information from cell phone companies’ business records. As Thomas pointed out, the Fourth Amendment protects individuals’ right to be secure in their “persons, homes, properties, and effects,” which means that individuals do not “have Fourth Amendment rights in someone else’s property.” Additionally, he noted, the “Fourth Amendment cannot be translated into a general constitutional ‘right to privacy.’”

Other instances mentioned by Magnet of Thomas’s rejection of the “living Constitution” include the Court’s abortion jurisprudence and its early campaign-finance reform decisions. His summation: “These opinions, Thomas’s best, add up to a sweeping critique of what the Court, sitting as a permanent constitutional convention and legislating from the bench with ample audacity, over seven decades, has wrought.”

The book’s concluding chapter is somewhat of a disappointment. It recapitulates neither Thomas’s life nor his works, offering instead a summary of Alexis de Tocqueville’s concern in Democracy of America about what we call today the administrative state. While Thomas would no doubt agree with the great French thinker, Magnet provides no supporting quotations from him. Then, too, the concluding comparison of the individual responsibility themes of My Grandfather’s Son to the victimology themes of Barack Obama’s The Audacity of Hope does not add much to what is, over all, a splendid book about Clarence Thomas, an inspiring man and inspiring jurist.

Ralph Rossum

Ralph Rossum is the Salvatori Professor of Political Philosophy & American Constitutionalism at Claremont McKenna College. He is the author of Antonin Scalia’s Jurisprudence: Text and Tradition (University Press of Kansas, 2006).