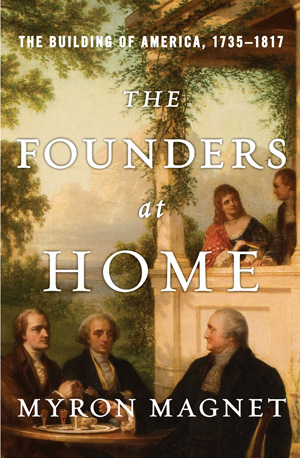

Through the Founders’ own voices — and in the homes they designed and built to embody the ideal of domestic happiness they fought to achieve — we come to understand why the American Revolution, of all great revolutions, was the only enduring success.

The Founders were vivid, energetic men, with sophisticated worldviews, and this magnificent reckoning of their successes draws liberally from their own eloquent writings on their actions and well-considered intentions. Richly illustrated with America’s historical and architectural treasures, this volume also considers the houses the Founders built with so much care and money, for they are revealing embodiments of the ideal of life they strove to bring into being. That so many great thinkers — Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Jefferson, John Jay, the Lees of Stratford Hall, and polemicist William Livingston — came together to accomplish what rightly seemed to them almost a miracle is a standing historical mystery, best understood by pondering the men themselves and their profound and world-changing ideas.

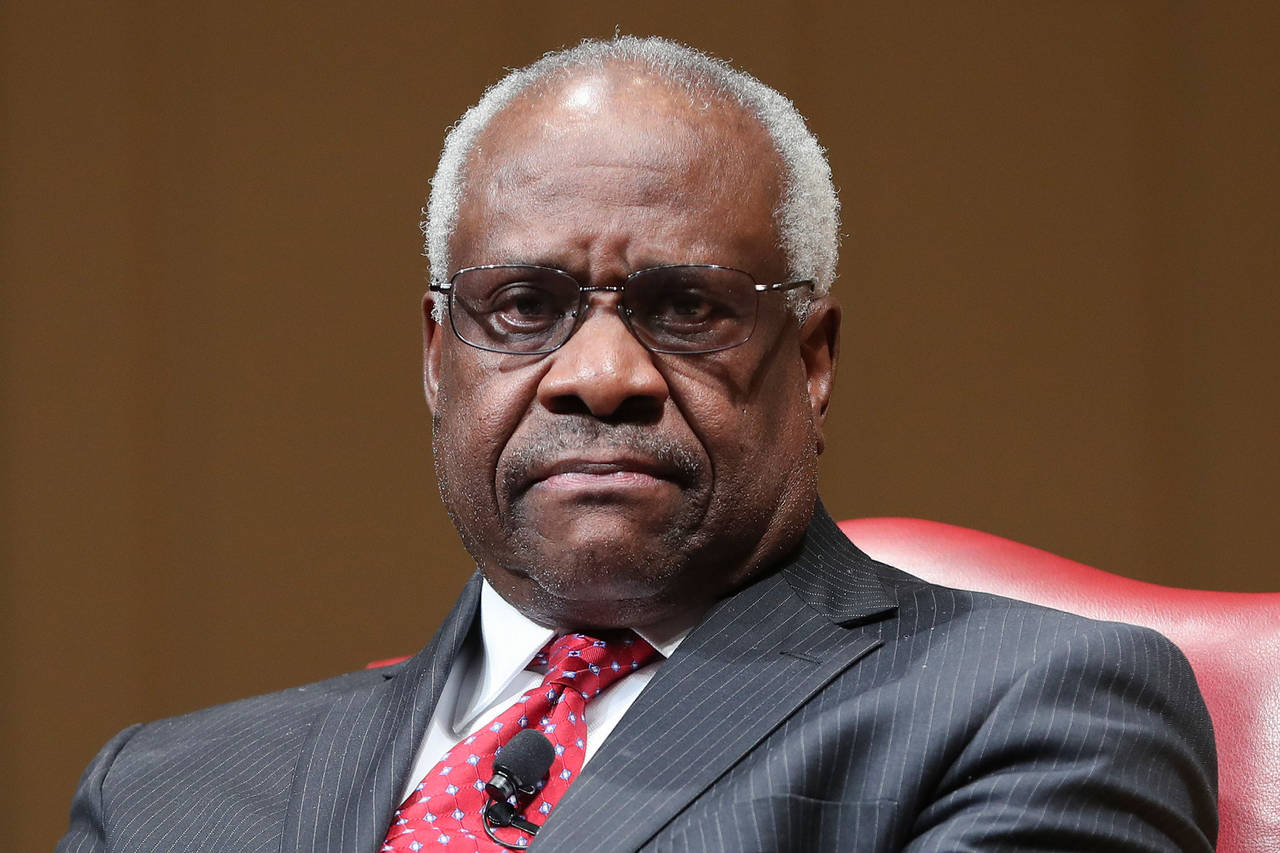

Through impressive research and an intimate understanding of these iconic patriots, award-winning author Myron Magnet offers fresh insight on why the American experiment resulted in over two centuries of unexampled freedom and prosperity.

Praise for The Founders

“The Founders at Home is rich in insight, wit, and wisdom about the men who created America. It’s superb — a pleasure to read on every page.” — Thomas Fleming, author of The Intimate Lives of the Founding Fathers

“The Founders at Home is a fascinating exploration of America’s founding fathers at the most intimate level. Highly original and intensely absorbing — Myron Magnet has produced an outstanding work of historical research.” — Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

“Myron Magnet has produced an excellent book from this excellent idea: We can better understand the Founders, who shaped how we live, if we better understand how they lived in the homes they designed and social circles that radiated from those homes. The American Revolution, he argues, was a success because of its moderation, and this virtue suffused the Founders’ lives.” — George F. Will, author of One Man’s America: The Pleasures and Provocations of Our Singular Nation

“Americans have long admired our Founders from a respectful distance. Now author Myron Magnet pulls us closer, into the framers’ homes and minds, so that we suddenly see not only what drove them but also how very much we share with those first Americans. Accurate, skillful, and utterly charming.” — Amity Shlaes, author of The Forgotten Man

“The Founders of the American Revolution avoided the excesses of other major revolutions, not just because of their seminal ideas but also because they were practical, good men, both at work and at home. Myron Magnet, in this strikingly original thesis, shows how the protection of liberty and property were natural extensions of the way the Founders organized their families and homes. We owe him thanks for this timely reminder that how we live and what we think should not be antithetical, but properly complementary.” — Victor Davis Hanson, author of A War Like No Other

“This is a beautiful, entertaining, and inspiring book.” — Richard Brookhiser, author of James Madison

Reviews of The Founders

“His exceedingly well-written and richly documented narrative builds excitement like the best of tales told around a campfire. . . . Magnet masterfully conveys the often halting steps the founders took as they moved toward the creation of our democracy by tapping lavishly into their own recorded words, a reminder both of what very good writers some of them were, and how lucky we were as a nation to have been born in the high noon of the Enlightenment. . . . With “The Founders at Home,” he has deepened our understanding of the worldview of our most esteemed political ancestors.” — Rosemary Michaud, Charleston Post and Courier

“An excellent and fluid writer, Magnet succeeds in proving his point that these were more than residences; they were an expression of the personalities of their remarkable owners. The Founders at Home provides an interesting, entertaining, and informative way of looking at their lives and their world.” — John Steele Gordon, Commentary

“This is a volume that will be right at home on the bookshelf of any reader fascinated by the Founders, their lives and their world.” — Alan Wallace, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

“He only recently visited Mount Vernon and Monticello for the first time. That visit and others have had a happy result, his book The Founders at Home: The Building of America, 1735–1817 .” — Michael Barone, The New Criterion

“Entertaining and illuminating. . . . Myron Magnet has done an exemplary job of portraying our fascinating founders both as remarkable individuals and as members of a flawed and quarrelsome team that still somehow managed to give life and meaning to the America we are blessed with today.” — Aram Bakshian, Jr., The American Spectator

“The “more a man drinketh of the world,” Francis Bacon wrote, “the more it intoxicateth.” Of all the worldly pleasures, power may be the most intoxicating, not least because it can command so many other felicities. Yet Magnet’s founders, deep as they drank of power, stayed sober. It helped, certainly, that, so far from looking on politics as a road to perfection, the founders regarded it as a necessary evil. Magnet illuminates the predicament of John Jay, who found the moral compromises of politics peculiarly painful, with an apposite quotation from Max Weber’s essay “Politics as a Vocation”: “he who lets himself in for politics, that is, for power and force as means, contracts with diabolical powers.”

Magnet’s book is full of such apercus; it is the work of a scholar who, trained in the old Western tradition of humane letters, has brought not only a lifetime of learning but also a rich fund of general experience to bear on the meaning and significance of the founding of the American Republic.” — Michael Knox Beran, The Claremont Review of Books

“America’s first chapter as a nation was written by many statesmen, and usually all we read are their letters, but Myron Magnet reads their houses in ‘The Founders at Home.’ As someone who has lived in two historic residences, the Texas Governor’s Mansion and the White House, I am fascinated by how the Founders’ ideas were represented through architecture, by what was preserved for posterity and what was disturbed.” — Laura Bush, The Wall Street Journal

Strict Constructions

Washington died land-rich but cash-poor. Hamilton apologized to his creditors for the paucity of his estate.

Book Review: The Founders at Home

By Myron Magnet

Norton, 472 pages, $35

Nov. 9, 2013

Does the world need yet another book on the American Founders? Yes, indeed: this one.

To the familiar story of protest, revolution and constitution-making, Myron Magnet adds hearth and home. He blends political theory and historical narrative with guided tours of William Livingston’s Liberty Hall, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, John Jay’s Homestead and James Madison’s Montpelier, among other patriot residences. We are reminded that the inventors of America had mortgages, too.

Mr. Magnet is an accomplished member of the cast of amateurs who have picked up the popular-history franchise that the American academic community tossed away. The great historians of yesteryear—John C. Miller, Samuel Eliot Morison, Robert H. Ferrell, Perry Miller—were scholars who wrote for all of us. Their books afford as much pleasure as instruction. Making proper allowances for a few shining exceptions, today’s tenured faculty members write mainly for one another.

Mr. Magnet is himself a kind of recovering Ph.D. Seeing the light some years ago, he went to work for Fortune magazine and later edited the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal, where he is now editor-at-large. His book is a labor of love.

In these pages, love of city vies with love of country. Mr. Magnet is the kind of New Yorker who regards his hometown as the one suitable place for the finalists in life’s competition to shine. Long before the Statue of Liberty rose in New York Harbor, Manhattan welcomed brains and beauty. Religion was no sticking point; talent was what mattered.

Mr. Magnet roots for the Founders who were prepared to lay down a national version of the New York welcome mat—”Opportunity America,” he calls it. He wags a finger at the Tories, Francophiles or slave drivers who opposed that meritocratic ideal. Between Federalists like Washington and Hamilton, on the one hand, and Republicans like Jefferson and Madison, on the other, he’s all for the former. He prefers British constitutionalism to the French guillotine, as—we tend to forget—not every American did in 1798.

“The Founders at Home” tells its story chronologically. The narrative begins in 1735 with William Livingston, a New York firebrand who broadcast the libertarian ideas of John Locke. It ends in 1817 with the post-presidential twilight of James Madison and his captivating wife, Dolley. In between come the Lees of Virginia—including “Light Horse Harry” and Arthur Lee, the first a dashing cavalryman, the second a key American agent in Europe—as well as Washington, Jay, Hamilton and Jefferson.

The narrative tissue connecting architecture and political theory is the oft-told story of the American Founding. Washington’s winter at Valley Forge, Hamilton’s affair with Maria Reynolds and Madison’s flight from the White House during the War of 1812 are among the familiar tales that Mr. Magnet tells all over again.

At first you wonder if he wasn’t being paid by the word. Generally, a mob is poorly behaved. There has never been a civil one. But Mr. Magnet’s mobs are, redundantly, “obstreperous” or “unruly.” Similarly, conquest is “blood-drenched,” and the enemy is “vengeful.” But either the Magnet style grew on me or the author found his better voice. By and by he writes of Hamilton, tautly: “He saw complex things at a glance, saw them whole and saw their consequences.” And he gets off this sentence: “One of the silliest things ever said about a land settled by immigrants making a new start across the sea is that there are no second acts in American lives.”

Though Hamilton, the rags-to-renown financier, lawyer and progenitor of the New York Post, appears to be Mr. Magnet’s favorite, he is not the Founder who best ticks the author’s architectural boxes. It’s rather Jefferson, Hamilton’s sparring partner during the first administration of George Washington, whose dwelling place seems to typify both its owner and the times in which he lived. The “implacable spirit of Enlightenment inquiry pervades Monticello in a way that dawns on you only gradually as you walk through the rooms,” writes Mr. Magnet. “The house seems to be saying, as Goethe supposedly cried on his deathbed, More light!”

The author finds another message behind the gorgeous Monticello bricks. Jefferson was forever building, thinking better of what he had built, razing what he had put up and starting over again. Putting up and tearing down was also Jefferson’s approach to revolutionary France. Never mind the rubble, he said in so many words—and never mind the corpses, he did say in almost those words. The ancien régime must go, no matter what the cost or who should succeed it; long live the Revolution!

The author’s biographical sketches make a group portrait that is bigger and better than the sum of its parts. Individually, the Founders seem financially ill-starred. Collectively, they present a case study in the perils of leverage. Thus Washington died land-rich but cash-poor. Hamilton died apologizing to his creditors for the paucity of his estate. Jefferson and Madison, each once a member of the Southern slave oligarchy, died virtually broke. Many of the Founders left a country behind and little else.

Mr. Magnet chooses to wall off between parentheses the arresting fact that even the New Yorker John Jay owned slaves. Otherwise he meets head-on the contradiction between the words and deeds of the slave-owning Founders. He can barely stand to quote Madison’s attempt to justify the Grand Compromise of the Constitutional Convention that resulted in counting a slave as three-fifths of a human being for the purpose of apportioning congressional seats and taxes. And he positively gags at describing Madison’s attack on the free-wage system—what a cruel and dehumanizing way to organize production, insisted the slave-driving Father of the Constitution.

But as the Constitution lives and breathes, so does Mr. Magnet honor its father, drawing a felicitous architectural analogy. Madison’s ancestral home, Piedmont, had 22 rooms during the ex-president’s day. Successive owners tastelessly enlarged it to 55. Madison would have hardly recognized the place before a 21st-century restoration team got to work. “I couldn’t help thinking of the whole project as a metaphor for the restoration that Madison’s Constitution needs,” Mr. Magnet writes, “—a clearing away of some of the more vainglorious excrescences added on by twentieth-century modernizers, defacing the simple, classical restraint and balance of the original, which every stage of Madison’s alterations had preserved.”

This is one of the few explicit comparisons that Mr. Magnet makes between what the Founders’ intended and what posterity has wrought. To a man, the architects of the new republic put a premium on civic virtue. No constitution—”no mound of parchment”—could save a debauched people from itself, Washington said. Jay warned against “political mountebanks” and, citing Cicero, added a warning against the demagogue’s “kind of liberality which involves robbing one man to give to another.” Madison, in Federalist Paper 57, reminded the legislature not to carve out exceptions for itself in the laws it enacted for everybody. Hamilton took it “as a fundamental maxim, in the system of public credit of the United States, that the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment.”

Mr. Magnet seems to have chosen not to draw lessons about 21st-century politics but rather to write history for its own sake. If so, he must have been tempted to backslide. What would Madison have to say about the infamous opt-out that members of Congress and their staffs enjoy from the Affordable Care Act? The reader is left to imagine.

Perhaps each Founder would have his own opinion about life in America today. Franklin might thrill to Google, while Washington might not thrill to the hit reality-TV show “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo.” Alexander Hamilton would very likely cringe at the public debt, disconnected from anything resembling the “means of extinguishment,” as well as at the post-Nixon paper dollar, so similar in format to the worthless Continental.

Among all the Founders in Mr. Magnet’s gallery, I would be most interested in hearing from John Jay, who, along with Franklin and John Adams, negotiated the peace that ended the Revolutionary War. Jay served as president of the Continental Congress, as governor of New York (in which capacity, in 1799, he signed a bill to effect the gradual abolition of slavery in the Empire State) and as plenipotentiary to the Spanish court. After the war, he negotiated the eponymous Jay Treaty with Britain that cleared up a number of sensitive issues with the former mother country. He became the first chief justice of the United States. Declining President Adams’s offer of a second term as chief justice, he retired to his 600 acres in Bedford, N.Y., a distant New York City suburb. There he planted trees and looked after crops, cider presses, saw mills and—a moneymaker, it says here—a dairy operation.

Today at the Jay Homestead, according to Mr. Magnet, “all his furniture, still in the house, breathes the same republican gentleman’s solid simplicity.” The author relates that Jay was “the most devout of the Founders,” though he doesn’t say how he came to know that fact. What he does say is that the pious Jay worshiped at a jewel box of a church near his farm in the company of his dog, Bob. He must have been some kind of dog. Certainly, in Mr. Magnet’s happy telling, John Jay was some kind of man.

—Mr. Grant, the editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, is the author

of “John Adams: Party of One.”

Founding Fathers’ Warnings Powerful Reminder Amid Government Crisis

By Michael Goodwin October 12, 2013

In his masterful new book on early America, author Myron Magnet uses concise biographies of George Washington and other Founders to illustrate why our revolution unleashed more than two centuries of freedom and prosperity. “The Founders at Home” is a work of scholarship and a labor of love, and offers vivid reminders of the courage of extraordinary individuals who birthed a new idea on Earth.

Take, for instance, the back-stabbing rivals trying to oust Washington as head of the Continental Army. Even as soldiers were leaving bloody footprints in the snow at Valley Forge, their commander had to defend himself against a vicious campaign by supposed comrades. Imagine if they had succeeded.

Or consider the unsentimental wisdom of John Jay, the diplomat who negotiated the treaty for independence with Great Britain and later became the first chief justice. Jay warned against the false “nostrums and prescriptions” of the ambitious and greedy, and urged his countrymen to “take men and things as they are.” Otherwise, he wrote, “the knaves and fools in this world are forever in alliance,” and self-government was doomed.

Magnet’s warts-and-all tour is so seductive in part because of our current troubles. Despite the success of the Founders’ grand experiment, events in Washington and around the world have many Americans fearing we are headed for a crack-up.

The fear provokes a wish we had a Washington or a Jefferson to guide us now. But the genius of Magnet’s book is that the “home” in the title refers not only to the actual homes the Founders built, many of which still stand, but also to the profound personal responsibility they felt to their new nation.

At enormous risk and cost, they created a model of patriotism that is not reserved for great men with lofty responsibilities. Their examples still matter because American exceptionalism ultimately is about ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

It is not enough to complain about our leaders and declare a pox on both their houses. We the people are sovereign and get the government we deserve. If bums are running the country, look in the mirror.

As I have said, my vote for Barack Obama in 2008 was a terrible mistake. I erred in hoping he would be what he promised to be instead of, as John Jay warned 200 years ago, what he actually was. Sadly, the rampant corruption and incompetence of his administration reveals the real Barack Obama, no matter what he says or whom he blames.

Others probably feel ashamed of their votes for Speaker John Boehner or Majority Leader Harry Reid. Their behavior also reminds us that voting carries consequences.

This does not mean that political strife is the problem. In fact, the system of checks and balances is based on the Founders’ assumption that human nature would be guided by self-interest, and that the clash of interests would produce a result that fairly represents the will of the people and the common good of the country.

But, obviously, something is broken. The balance between rights and responsibilities has been shattered and the nation’s character diminished.

The same sense of self-gratification and entitlement that infects our culture rules our politics. Elements of our government are as vulgar as the worst of our entertainment.

As Magnet shows, the Founders predicted the peril we now face. Washington saw the Constitution as but a piece of parchment that depended upon “virtue in the body of the people.”

If that virtue was eroded, he warned, by a “corruption of morals, profligacy of manners and listlessness for the preservation of the natural and unalienable rights of mankind,” America would degenerate into tyranny.

No, we are not there yet, but ask yourself this: Where on the spectrum of our history are we?

Are the founding virtues still intact, or has their spirit been eroded by the “corruption of morals”?

Are we closer today to the ideals of liberty, or to the tyranny the Founders warned would follow the death of those ideals?

Each of us should answer those questions and act accordingly. After all, accepting individual responsibility is the foundation of American exceptionalism.

DECEMBER 31, 2013, ISSUE

Built to Last

The Founders at Home: The Building of America, 1735–1817, by Myron Magnet (Norton, 481 pp., $35)

By Richard Brookhiser

Monticello

Monticello

Has the Founders’ revival peaked? The big bios of the big names, now in big paperback editions, still sit on bookstore shelves, like Pleistocene megafauna, yet the subject stimulates feelings of both satiety and constriction. We have read a lot about the most famous Founders — the first four presidents (Washington to Madison) plus the two others who made it into our wallets (Hamilton, Franklin). The rest, however, struggle in their backwash; although there have been good recent books about Sam Adams, John Dickinson, Nathanael Greene, and others, they never seem to make 18th-Century Page Six.

Myron Magnet has found a delightful way out of this cul-de-sac. The Founders at Home is subtitled “The Building of America, 1735–1817.” “Building” is a pun: All the men he writes about left homes that, centuries later, are still intact and visitable. But, by a shrewd selection of subjects, Magnet also covers the construction of a country, from first thoughts to finishing touches — from the Zenger trial to the Battle of New Orleans. His cast of characters allows him to erase the dichotomy between overexposure and obscurity. The heavyweights are well represented: Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison. But joining them are Founders most of us have barely or never heard of: William Livingston, the Lees of Stratford Hall, sober John Jay. The Founders at Home gives the pleasures of biography, while putting us back in the texture and complexity of a world.

Begin with the little-knowns. William Livingston, born in 1723, was a sprig of a wealthy Colonial New York clan. The Livingstons jockeyed for position in the elected assembly while baiting Crown-appointed governors. Much of their tussling was conducted in print: The Livingstons backed John Peter Zenger, the printer whose 1735 acquittal on a charge of seditious libel would unshackle Colonial American newspapers. In 1752, young William Livingston, a successful lawyer, launched a journal of his own, The Independent Reflector, to comment on a proposal to found a taxpayer-supported Anglican college in New York City. New York was religiously diverse even then, with all sorts of Protestants and a handful of Jews. Livingston hated the scheme. A “tax ought to be considered as the voluntary Gift of the People,” he wrote. “The civil Power hath no Jurisdiction over the Sentiments or Opinions of the Subject, till such Opinions break out into Actions prejudicial to the Community.” The college — King’s College, now Columbia — got founded, but Livingston had injected a dose of applied Locke into the American bloodstream.

The Lees were a brood of proud, eccentric gentry reared at Stratford Hall, 70 miles down the Potomac from Alexandria. In the musical about the Continental Congress, 1776, Richard Henry Lee is depicted as a genial boob, Jethro Bodine with manners. Magnet gives us the real deal. R.H., as he was known to his family, was hunting swans one winter day in 1768 “when his gun blew up, blowing the four fingers off his left hand. Ever after, he wore a specially made black silk glove to cover his disfigurement.” But it made him so cool. “In time, he practiced gesturing dramatically with it, which, with his Roman nose, high forehead, tall, gaunt frame, [and] aristocratic bearing . . . added to his command as an orator.” R.H.’s great gesture was to move, in June 1776, “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.”

R.H.’s younger brother Arthur, studying medicine and law in Britain, became a friend of James Boswell and John Wilkes and a propagandist for the American cause, then moved on to diplomacy in Paris, where he annoyed Benjamin Franklin by complaining that the American mission there had been penetrated by spies (he was right). The brothers had a cousin, Henry, one of Washington’s dashing cavalry officers. In peacetime he made up for the thrill of battle with an orgy of land speculation that sent him to debtor’s prison. (His son, Robert E., would become famous in a later war.)

Stratford Hall, as befits such a family, looks odd. Its lines strike me as rather East German, as if it were a factory for making surveillance equipment. But the bricks of which it is built give it a warm, rich glow.

Of the prima donnas in The Founders at Home, perhaps the two most striking are Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, in part because of their homes. Magnet is a partisan: He admires the young colonel from St. Croix, and he seems rather suspicious of Mr. Jefferson. But when their houses face off, Monticello wins — though it is a near-run thing.

Hamilton, whom Magnet calls “the upwardly mobile young immigrant of dubious parentage,” sought security as well as fame in his adopted country. After retiring from his post as the United States’ first Treasury secretary, he felt his private career as a lawyer had prospered enough to allow him to build a summer house, which he called the Grange, on the northern heights of Manhattan (then countryside). Hamilton enjoyed it for only a few years before dying in his duel with Aaron Burr. As the land was developed, the Grange was moved, and it sat for over a century wedged between a church and an apartment building. In 2008, the National Park Service moved it to a nearby park, restoring its original colors and mirrored doors: “A perfect embodiment,” writes Magnet, “of his elegant, logical, complicated Enlightenment mind.”

The premier Enlightenment house of the Founding, though, has to be Monticello. It “seems to be saying,” Magnet writes, “as Goethe supposedly cried on his deathbed, More light! It’s not just that there are few dark corners in a house made up of so many demi-octagons, but that Jefferson has designed it so that light pours in from everywhere — through oversized, triple-hung windows and lots of them, through glass doors, through multiple skylights made up of glass louvers . . . all reflected and bounced back across the lofty rooms by mirrors everywhere.”

But even Monticello has its darkness. Two wings connect the main house to flanking pavilions; but the wings “are in fact covered passages that lead out of the cellar of the house and contain the semi-subterranean kitchen, dairy, and other rooms for those who waited on Jefferson. Since those latter were slaves, it’s hard not to [think] of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, with its airy, playful creatures of light enjoying the surface of the earth, while the dark Morlocks toil hidden.”

Magnet rubs Jefferson’s nose in this, but ends, as he must, by giving him his due, for it was to Jefferson that Lincoln would turn to explain what the Civil War was about. Writes Magnet: “The abstraction, not the history, was at that moment our true national identity. And in the ever-growing consciousness of man’s freedom that is the true meaning of history . . . so it became.”

Perhaps the best of Magnet’s portraits is that of his man in the middle, John Jay. There he is, on the cover of your college paperback of The Federalist Papers. Yet when you open it, as you surely do, you notice that he wrote only five of the 85 essays (he fell sick early on, then was knocked unconscious in a New York City riot). You may remember that he negotiated a treaty that bears his name, and for which half the country execrated him. What does this man have to offer us?

A lot that needed doing and that was not pretty. Jay’s hardest service came during the Revolution. Son of a family of New York Huguenot merchants, he ran the ominously named Committee for Detecting Conspiracies. New York was split between patriots and loyalists, and each side had guerrilla enforcers (Skinners and Cow-boys, respectively). “Punishments must of course become certain,” Jay wrote, “and Mercy dormant, a harsh System repugnant to my Feelings, but nevertheless necessary.” He also ran a Hudson Valley spy ring, whose adventures he later recounted to a young family friend, James Fenimore Cooper, who turned them into his first bestseller, The Spy.

Later in the war, Jay served as a diplomat in Spain and France. There he learned that allies can be as bad as enemies. When it came time to negotiate the Treaty of Paris, he encouraged Britain to give the United States a good deal, to keep it independent of France. Treaties, he explained, “had never signified any thing since the World began.” The former colonies and former mother country should base a new relationship on common interest.

He directed the same clear gaze on the lacrimae rerum. The letter he wrote Hamilton’s father-in-law after his friend was shot is saved from bitterness only by grace. “The philosophic topics of consolation are familiar to you, and we all know from experience how little relief is to be derived from them. May the Author and only Giver of consolation be and remain with you.”

The pictures in Magnet’s book are splendid, 32 pages in full color. Read about these houses, and their owners — you will find a mix of men who did their country proud.

Book Details

November 11, 2013, W. W. Norton & Company

Hardcover, 448 pages, with 32 pages of color illustrations

ISBN 9780393240214

Also available in e-book and audiobook editions.